Week 9 [Fri, Oct 13th] - Topics

Detailed Table of Contents

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Previously, you learned about class and object diagrams. Let's touch on another variant of class diagrams that complements the first two. The good news is that it is simply a subset of the notation that you already know.

Can explain object oriented domain models

The analysis process for identifying objects and object classes is recognized as one of the most difficult areas of object-oriented development. --Ian Sommerville, in the book Software Engineering

Class diagrams can also be used to model objects in the (i.e. to model how objects actually interact in the real world, before emulating them in the solution). Class diagrams that are used to model the problem domain are called conceptual class diagrams or OO domain models (OODMs).

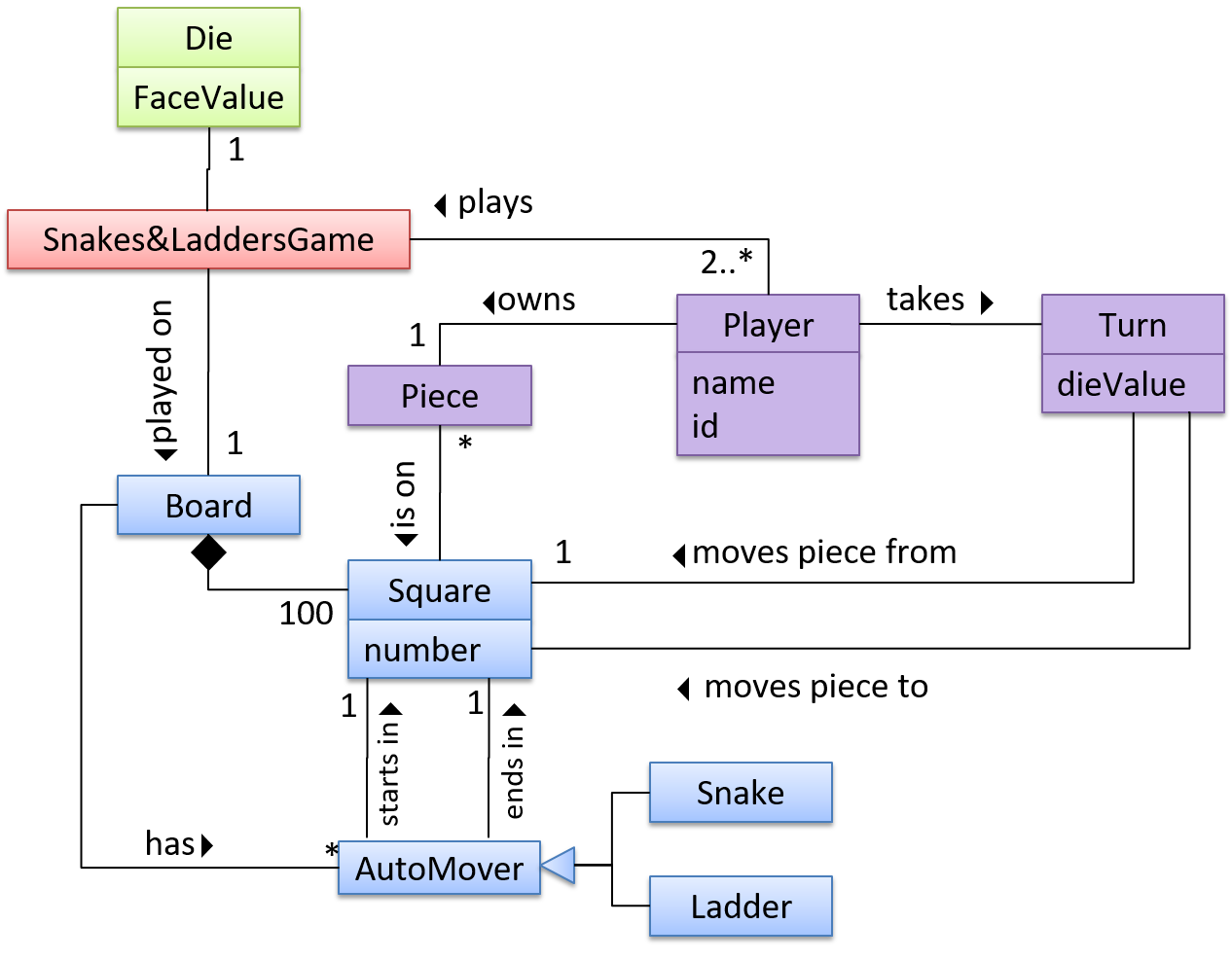

The OO domain model of a snakes and ladders game is given below.

Description: The snakes and ladders game is played by two or more players using a board and a die. The board has 100 squares marked 1 to 100. Each player owns one piece. Players take turns to throw the die and advance their piece by the number of squares they earned from the die throw. The board has a number of snakes. If a player’s piece lands on a square with a snake head, the piece is automatically moved to the square containing the snake’s tail. Similarly, a piece can automatically move from a ladder foot to the ladder top. The player whose piece is the first to reach the 100th square wins.

OODMs do not contain solution-specific classes (i.e. classes that are used in the solution domain but do not exist in the problem domain). For example, a class called DatabaseConnection could appear in a class diagram but not usually in an OO domain model because DatabaseConnection is something related to a software solution but not an entity in the problem domain.

OODMs represents the class structure of the problem domain and not their behavior, just like class diagrams. To show behavior, use other diagrams such as sequence diagrams.

OODM notation is similar to class diagram notation but omit methods and navigability.

Follow up notes for the item(s) above:

Here is an example that shows the steps of drawing an OODM to match a given problem domain.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Activity diagrams is the last UML diagram type you'll be learning in this course, and probably the easiest and most intuitive of the lot. You've heard about 'flow charts', right? Well, this is the UML equivalent of that.

Can use basic-level activity diagrams

Software projects often involve workflows. Workflows define the flow in which a process or a set of tasks is executed. Understanding such workflows is important for the success of the software project.

Some examples in which a certain workflow is relevant to software project:

A software that automates the work of an insurance company needs to take into account the workflow of processing an insurance claim.

The algorithm of a piece of code represents the workflow (i.e. the execution flow) of the code.

UML Activity Diagrams → Introduction → What

UML Activity Diagrams → Basic Notation → Linear Paths

UML Activity Diagrams → Basic Notation → Alternate Paths

UML Activity Diagrams → Basic Notation → Parallel Paths

Follow up notes for the item(s) above:

Here are some examples showing the steps of drawing an activity diagram to match a given workflow.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

A few weeks ago, you learned how to interpret UML diagrams. More recently, you learned how to draw diagrams to match code. There's a third use of models: as an aid for coming up with a design before the code is written.

While this course doesn't ask you to come up with detailed designs before writing code (i.e., our approach leans closer to the agile design rather than the full design upfront approach), this third use of models come in handy at times. Let's learn a bit about that too.

Can explain how modeling can be used before implementation

You can use models to analyze and design software before you start coding.

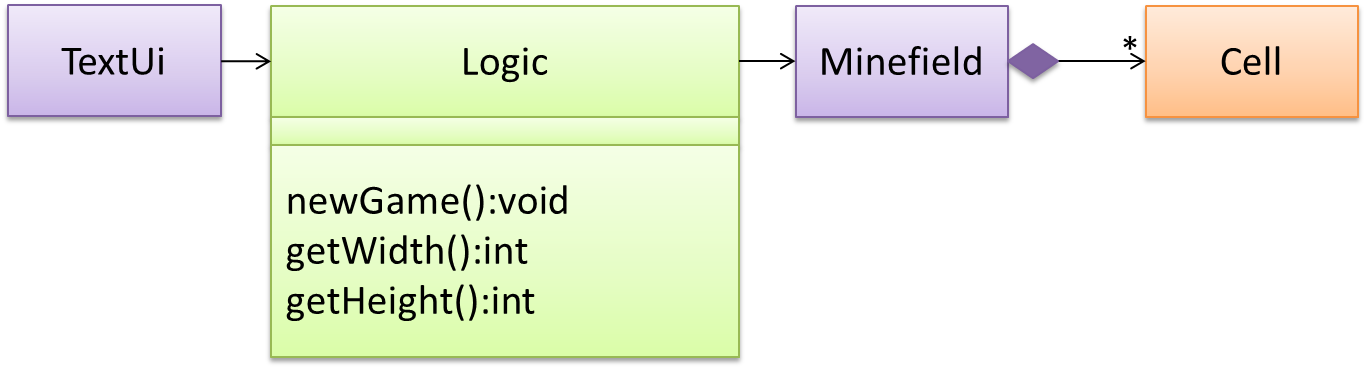

Suppose you are planning to implement a simple minesweeper game that has a text based UI and a GUI. Given below is a possible OOP design for the game.

Before jumping into coding, you may want to find out things such as,

- Is this class structure able to produce the behavior you want?

- What API should each class have?

- Do you need more classes?

To answer these questions, you can analyze how the objects of these classes will interact with each other to produce the behavior you want.

Can use simple class diagrams and sequence diagrams to model an OO solution

As mentioned in [Design → Modeling → Modeling a Solution → Introduction], this is the Minesweeper design you have come up with so far. Our objective is to analyze, evaluate, and refine that design.

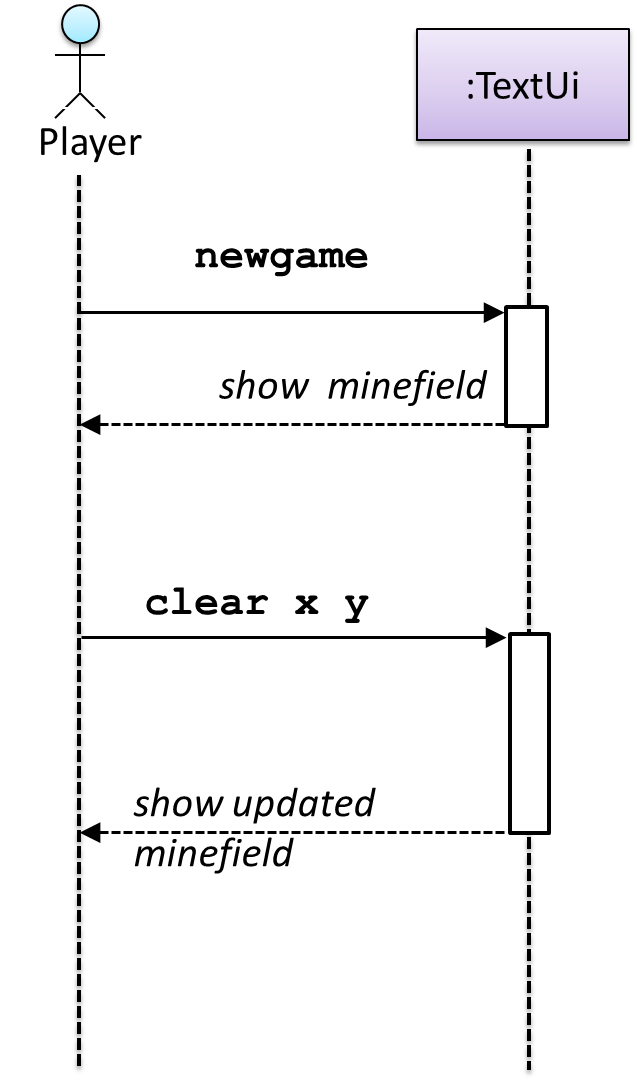

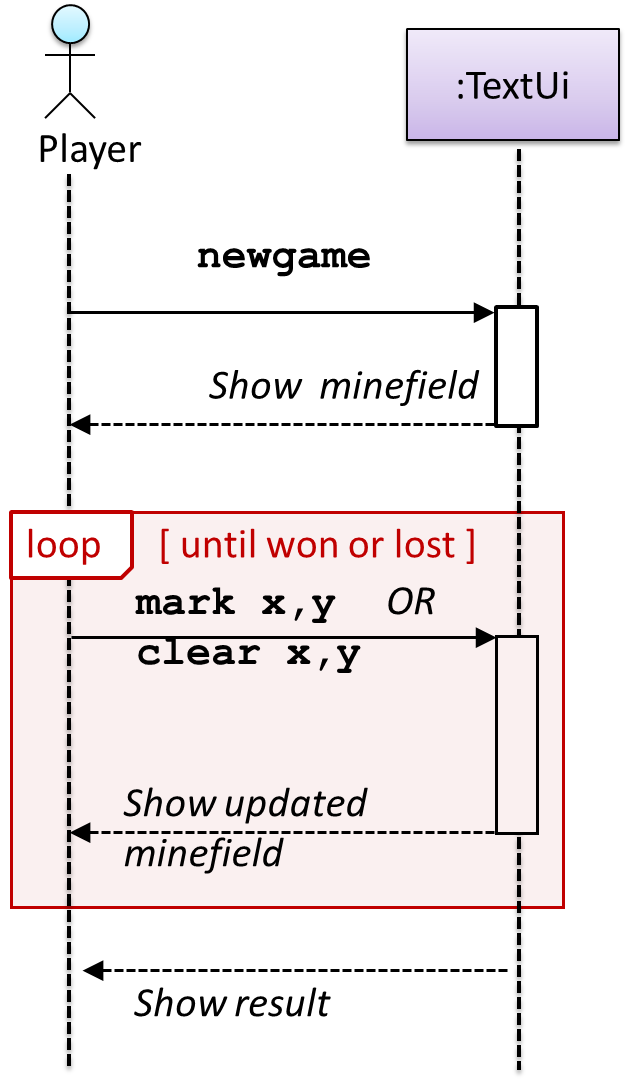

Let us start by modeling a sample interaction between the person playing the game and the TextUi object.

newgame and clear x y represent commands typed by the Player on the TextUi.

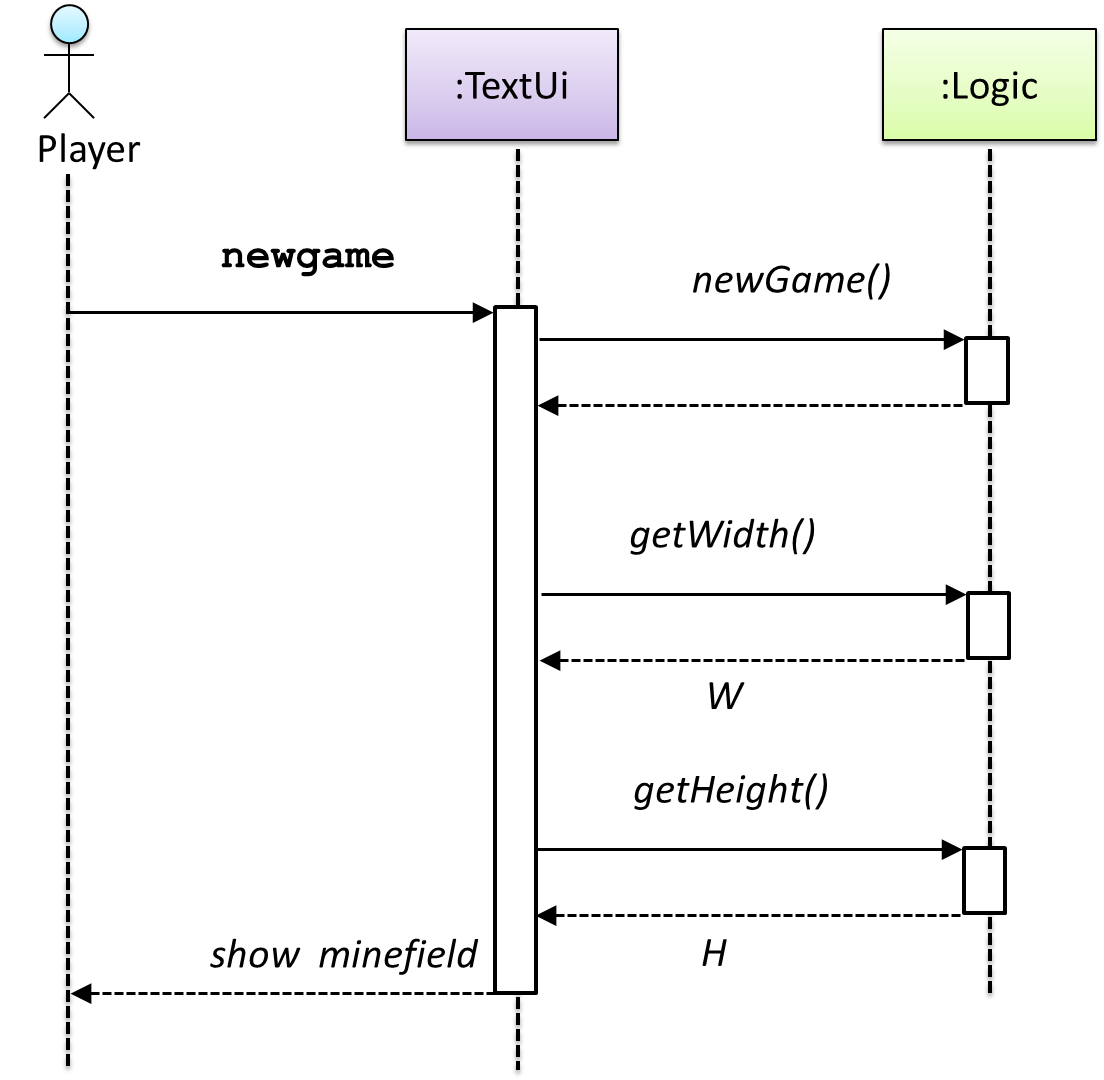

How does the TextUi object carry out the requests it has received from the player? It would need to interact with other objects of the system. Because the Logic class is the one that controls the game logic, the TextUi needs to collaborate with Logic to fulfill the newgame request. Let us extend the model to capture that interaction.

W = Width of the minefield; H = Height of the minefield

The above diagram assumes that W and H are the only information TextUi requires to display the minefield to the Player. Note that there could be other ways of doing this.

The Logic methods you conceptualized in our modeling so far are:

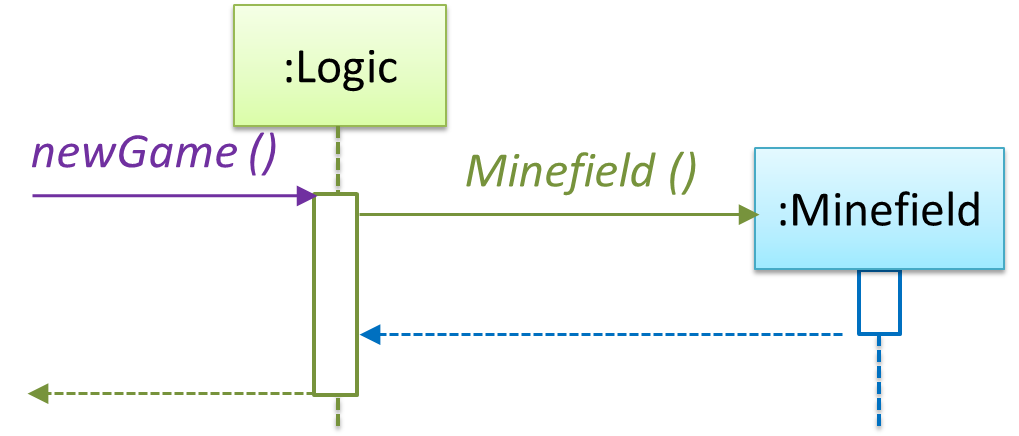

Now, let us look at what other objects and interactions are needed to support the newGame() operation. It is likely that a new Minefield object is created when the newGame() method is called.

Note that the behavior of the Minefield constructor has been abstracted away. It can be designed at a later stage.

Given below are the interactions between the player and the TextUi for the whole game.

Note that can be used when discovering/defining the architecture-level APIs.

Defining the architecture-level APIs for a small Tic-Tac-Toe game:

Guidance for the item(s) below:

You've already encountered architecture diagrams in your tP. Pretty soon, you might have to update that diagram to match your new product. Given below are just a brief note about drawing architecture diagrams.

Can draw an architecture diagram

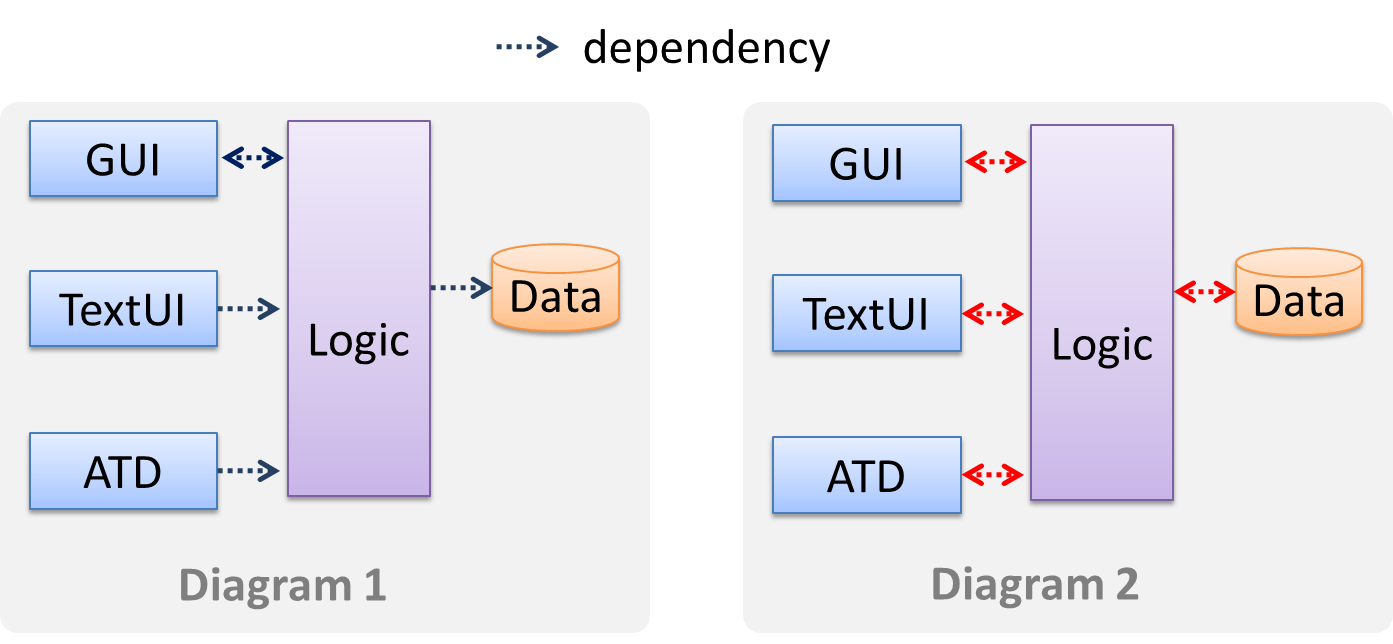

While architecture diagrams have no standard notation, try to follow these basic guidelines when drawing them.

Minimize the variety of symbols. If the symbols you choose do not have widely-understood meanings e.g. A drum symbol is widely-understood as representing a database, explain their meaning.

Avoid the indiscriminate use of double-headed arrows to show interactions between components.

Consider the two architecture diagrams of the same software given below. Because Diagram 2 uses double-headed arrows, the important fact that GUI has a bidirectional dependency with the Logic component is no longer captured.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

These principles build on top of the design fundamentals you learned earlier (i.e., abstraction, coupling, cohesion).

Can explain separation of concerns principle

Separation of concerns principle (SoC): To achieve better modularity, separate the code into distinct sections, such that each section addresses a separate concern. -- Proposed by Edsger W. Dijkstra

A concern in this context is a set of information that affects the code of a computer program.

Examples for concerns:

- A specific feature, such as the code related to the

add employeefeature - A specific aspect, such as the code related to

persistenceorsecurity - A specific entity, such as the code related to the

Employeeentity

Applying reduces functional overlaps among code sections and also limits the ripple effect when changes are introduced to a specific part of the system.

If the code related to persistence is separated from the code related to security, a change to how the data are persisted will not need changes to how the security is implemented.

This principle can be applied at the class level, as well as at higher levels.

The n-tier architecture utilizes this principle. Each layer in the architecture has a well-defined functionality that has no functional overlap with each other.

This principle should lead to higher cohesion and lower coupling.

Can explain single responsibility principle

Single responsibility principle (SRP): A class should have one, and only one, reason to change. -- Robert C. Martin

If a class has only one responsibility, it needs to change only when there is a change to that responsibility.

Consider a TextUi class that does parsing of the user commands as well as interacting with the user. That class needs to change when the formatting of the UI changes as well as when the syntax of the user command changes. Hence, such a class does not follow the SRP.

Gather together the things that change for the same reasons. Separate those things that change for different reasons. ―- Agile Software Development, Principles, Patterns, and Practices by Robert C. Martin

Resources:

- An explanation of the SRP from www.oodesign.com

- Another explanation (more detailed) by Patkos Csaba

- A book chapter on SRP written by the father of the principle itself, Robert C Martin

Can explain Liskov Substitution Principle

Liskov substitution principle (LSP): Derived classes must be substitutable for their base classes. -- proposed by Barbara Liskov

LSP sounds the same as substitutability but it goes beyond substitutability; LSP implies that a subclass should not be more restrictive than the behavior specified by the superclass. As you know, Java has language support for substitutability. However, if LSP is not followed, substituting a subclass object for a superclass object can break the functionality of the code.

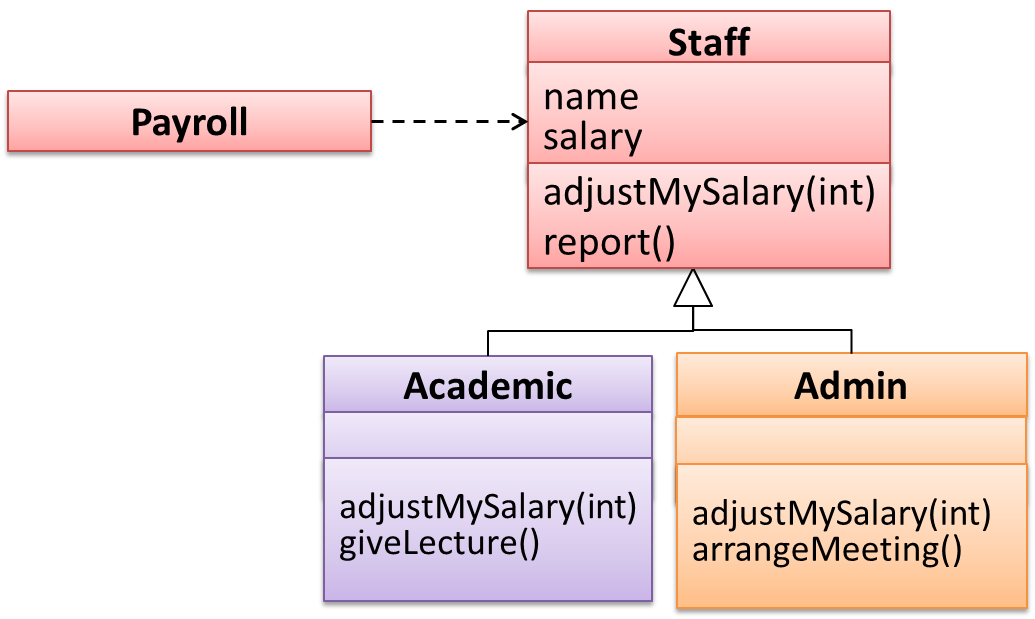

Suppose the Payroll class depends on the adjustMySalary(int percent) method of the Staff class. Furthermore, the Staff class states that the adjustMySalary method will work for all positive percent values. Both the Admin and Academic classes override the adjustMySalary method.

Now consider the following:

- The

Admin#adjustMySalarymethod works for both negative and positive percent values. - The

Academic#adjustMySalarymethod works for percent values1..100only.

In the above scenario,

- The

Adminclass follows LSP because it fulfillsPayroll’s expectation ofStaffobjects (i.e. it works for all positive values). SubstitutingAdminobjects forStaffobjects will not break thePayrollclass functionality. - The

Academicclass violates LSP because it will not work for percent values over100as expected by thePayrollclass. SubstitutingAcademicobjects forStaffobjects can potentially break thePayrollclass functionality.

Another example

Can explain open-closed principle (OCP)

The Open-Closed Principle aims to make a code entity easy to adapt and reuse without needing to modify the code entity itself.

Open-closed principle (OCP): A module should be open for extension but closed for modification. That is, modules should be written so that they can be extended, without requiring them to be modified. -- proposed by Bertrand Meyer

In object-oriented programming, OCP can be achieved in various ways. This often requires separating the specification (i.e. interface) of a module from its implementation.

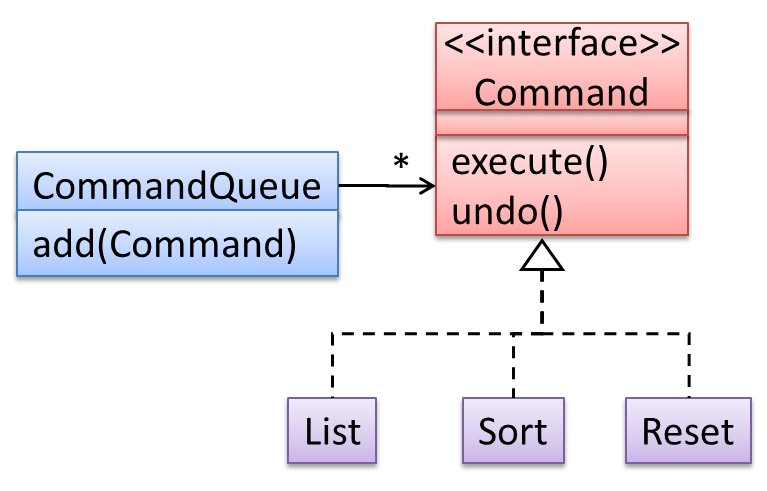

In the design given below, the behavior of the CommandQueue class can be altered by adding more concrete Command subclasses. For example, by including a Delete class alongside List, Sort, and Reset, the CommandQueue can now perform delete commands without modifying its code at all. That is, its behavior was extended without having to modify its code. Hence, it is open to extensions, but closed to modification.

The behavior of a Java generic class can be altered by passing it a different class as a parameter. In the code below, the ArrayList class behaves as a container of Students in one instance and as a container of Admin objects in the other instance, without having to change its code. That is, the behavior of the ArrayList class is extended without modifying its code.

ArrayList students = new ArrayList<Student>();

ArrayList admins = new ArrayList<Admin>();

Can explain the Law of Demeter

Law of Demeter (LoD):

- An object should have limited knowledge of another object.

- An object should only interact with objects that are closely related to it.

Also known as

- Don’t talk to strangers.

- Principle of least knowledge

More concretely, a method m of an object O should invoke only the methods of the following kinds of objects:

- The object

Oitself - Objects passed as parameters of

m - Objects created/instantiated in

m(directly or indirectly) - Objects from the

O

The following code fragment violates LoD due to the following reason: while b is a ‘friend’ of foo (because it receives it as a parameter), g is a ‘friend of a friend’ (which should be considered a ‘stranger’), and g.doSomething() is analogous to ‘talking to a stranger’.

void foo(Bar b) {

Goo g = b.getGoo();

g.doSomething();

}

LoD aims to prevent objects from navigating the internal structures of other objects.

An analogy for LoD can be drawn from Facebook. If Facebook followed LoD, you would not be allowed to see posts of friends of friends, unless they are your friends as well. If Jake is your friend and Adam is Jake’s friend, you should not be allowed to see Adam’s posts unless Adam is a friend of yours as well.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

If you liked the principles covered above, given below are a few more widely used principles most of which are optional in this course (they were moved to the optional topics in order to reduce the course workload).

The only examinable thing is the term SOLID principles.

Can explain SOLID Principles

The five OOP principles given below are known as SOLID Principles (an acronym made up of the first letter of each principle):

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Remember these three topics that we covered early in the course?

Can explain SDLC process models

Software development goes through different stages such as requirements, analysis, design, implementation and testing. These stages are collectively known as the software development life cycle (SDLC). There are several approaches, known as software development life cycle models (also called software process models), that describe different ways to go through the SDLC. Each process model prescribes a 'roadmap' for the software developers to manage the development effort. The roadmap describes the aims of the development stages, the outcome of each stage, and the workflow i.e. the relationship between stages.

Can explain sequential process models

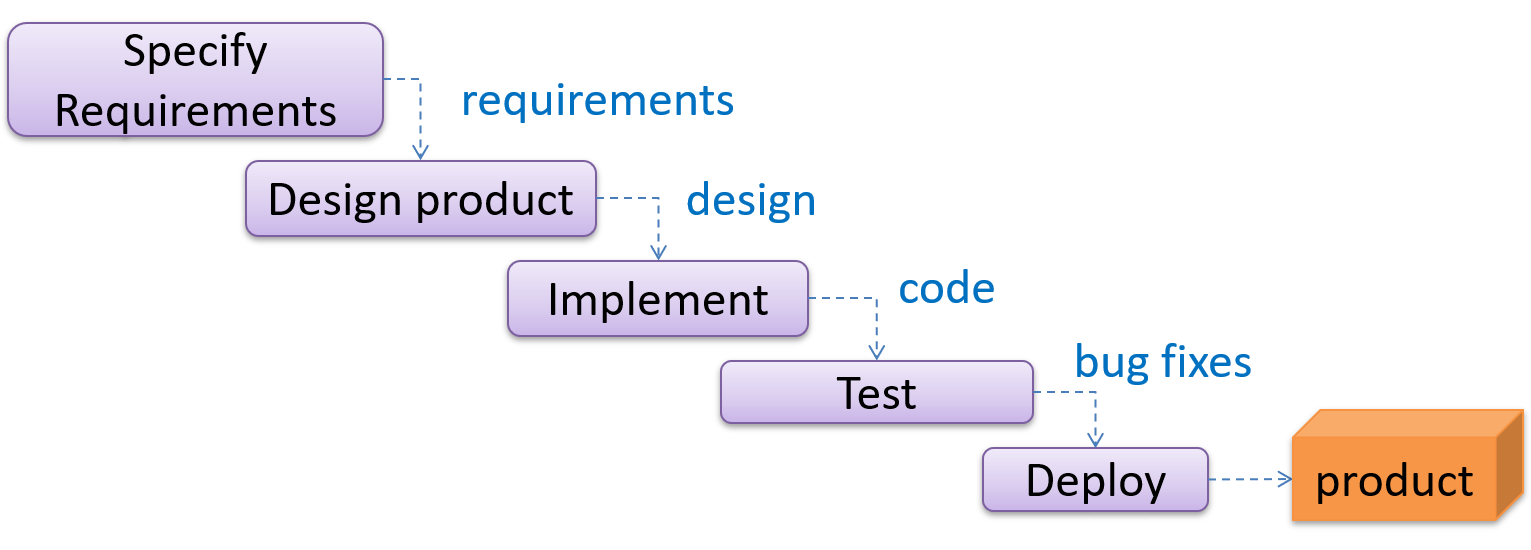

The sequential model, also called the waterfall model, views software development as a linear process, in which the project is seen as progressing through the development stages. The name waterfall stems from how the model is drawn to look like a waterfall (see below).

When one stage of the process is completed, it produces some artifacts to be used in the next stage. For example, the requirements stage produces a comprehensive list of requirements, to be used in the design phase.

A strict sequential model project moves only in the forward direction i.e., each stage is completed before starting the next. For example, once the requirements stage is over, there is no provision for revising the requirements later.

This model can work well for a project that produces software to solve a well-understood problem, in which case the requirements can remain stable and the effort can be estimated accurately. Furthermore, as each stage has a well-defined outcome, it is easy to track the progress of the project because one can gauge the project progress by monitoring which stage the project is in.

However, real-world projects often tackle problems that are not well-understood at the beginning, making them unsuitable for this model. For example, target users of a software product may not be able to state their requirements accurately at the start of the project, if they have not used a similar product before.

Can explain iterative process models

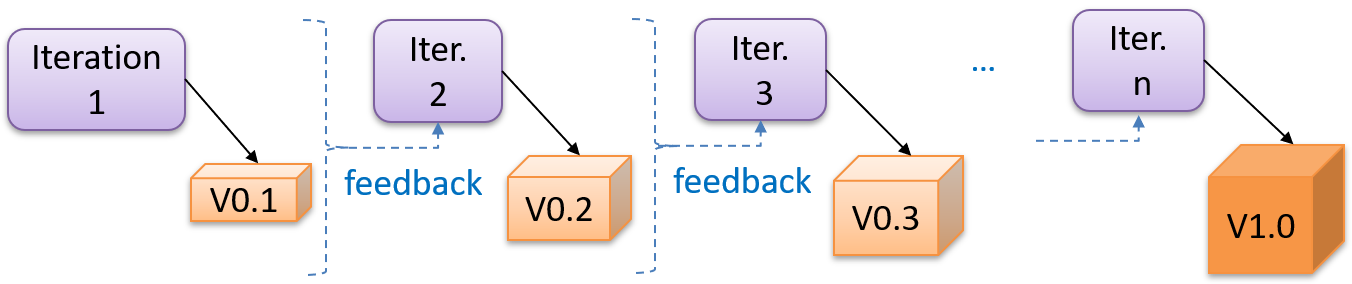

The iterative model advocates producing the software by going through several iterations. Each of the iterations could potentially go through all the stages of the SDLC, from requirements gathering to deployment.

Each iteration produces a new version of the product, building upon the version produced in the previous iteration. Feedback from each iteration is factored into the subsequent iterations. For example, if an implementation task took longer than expected, the effort estimate for a similar tasks in future iterations can be adjusted accordingly. Similarly, if a feature introduced in the current iteration was not well-received by target users, it can be removed or tweaked in the next iteration.

The iterative model can be done in breadth-first or depth-first approach.

- In the breadth-first approach, an iteration evolves all major components and all functionality areas in parallel i.e., most features and most will be updated in each iteration, producing a working product at the end of each iteration.

- In the depth-first approach, an iteration focuses on fleshing out only some components or some functionality area. Accordingly, early depth-first iterations might not produce a working product.

Taking a Minesweeper game as an example,

- breadth-first iterations will deliver a fully playable version early. These early versions may have primitive functionality, for example, a rudimentary text based UI, fixed board size, limited minefield layouts, etc. These functionalities (and corresponding components) will then be improved in later releases.

- an early depth-first iteration could deliver the full user interface (UI) but with no game logic at all. Alternatively, an early iteration could focus on just the logic for generating initial layouts of the minefield. Neither will be a playable version of the game but both can be used to collect early feedback (about the UI, and the initial minefield layouts, respectively) which can then be used to guide later iterations.

A project can be done as a mixture of breadth-first and depth-first iterations i.e., an iteration can contain some breadth-first work as well as some depth-first work, or, some iterations can be breadth-first while others are depth-first.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Let's continue that thread to learn about some SDLC process models that are commonly used in the industry.

Can explain agile process models

In 2001, a group of prominent software engineering practitioners met and brainstormed for an alternative to documentation-driven, heavyweight software development processes that were used in most large projects at the time. This resulted in something called the agile manifesto (a vision statement of what they were looking to do).

You are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.

Through this work you have come to value:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, you value the items on the left more.

-- Extract from the Agile Manifesto

Subsequently, some of the signatories of the manifesto went on to create process models that try to follow it. These processes are collectively called agile processes. Some of the key features of agile approaches are:

- Requirements are prioritized based on the needs of the user, are clarified regularly (at times almost on a daily basis) with the entire project team, and are factored into the development schedule as appropriate.

- Instead of doing a very elaborate and detailed design and a project plan for the whole project, the team works based on a rough project plan and a high level design that evolves as the project goes on.

- There is a strong emphasis on complete transparency and responsibility sharing among the team members. The team is responsible together for the delivery of the product. Team members are accountable, and regularly and openly share progress with each other and with the user.

There are a number of agile processes in the development world today. eXtreme Programming (XP) and Scrum are two of the well-known ones.

Can explain scrum

This description of Scrum was adapted from Wikipedia [retrieved on 18/10/2011], emphasis added:

Scrum is a process skeleton that contains sets of practices and predefined roles. The main roles in Scrum are:

- The Scrum Master, who maintains the processes (typically in lieu of a project manager)

- The Product Owner, who represents the stakeholders and the business

- The Team, a cross-functional group who do the actual analysis, design, implementation, testing, etc.

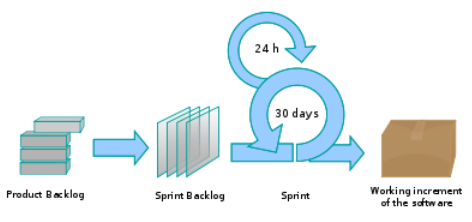

A Scrum project is divided into iterations called Sprints. A sprint is the basic unit of development in Scrum. Sprints tend to last between one week and one month, and are a timeboxed (i.e. restricted to a specific duration) effort of a constant length.

Each sprint is preceded by a planning meeting, where the tasks for the sprint are identified and an estimated commitment for the sprint goal is made, and followed by a review or retrospective meeting, where the progress is reviewed and lessons for the next sprint are identified.

During each sprint, the team creates a potentially deliverable product increment (for example, working and tested software). The set of features that go into a sprint come from the product backlog, which is a prioritized set of high level requirements of work to be done. Which backlog items go into the sprint is determined during the sprint planning meeting. During this meeting, the Product Owner informs the team of the items in the product backlog that he or she wants completed. The team then determines how much of this they can commit to complete during the next sprint, and records this in the sprint backlog. During a sprint, no one is allowed to change the sprint backlog, which means that the requirements are frozen for that sprint. Development is timeboxed such that the sprint must end on time; if requirements are not completed for any reason they are left out and returned to the product backlog. After a sprint is completed, the team demonstrates the use of the software.

Scrum enables the creation of self-organizing teams by encouraging co-location of all team members, and verbal communication between all team members and disciplines in the project.

A key principle of Scrum is its recognition that during a project the customers can change their minds about what they want and need (often called requirements churn), and that unpredicted challenges cannot be easily addressed in a traditional predictive or planned manner. As such, Scrum adopts an empirical approach—accepting that the problem cannot be fully understood or defined, focusing instead on maximizing the team’s ability to deliver quickly and respond to emerging requirements.

Daily Scrum is another key scrum practice. The description below was adapted from https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com (emphasis added):

In Scrum, on each day of a sprint, the team holds a daily scrum meeting called the "daily scrum.” Meetings are typically held in the same location and at the same time each day. Ideally, a daily scrum meeting is held in the morning, as it helps set the context for the coming day's work. These scrum meetings are strictly time-boxed to 15 minutes. This keeps the discussion brisk but relevant.

...

During the daily scrum, each team member answers the following three questions:

- What did you do yesterday?

- What will you do today?

- Are there any impediments in your way?

...

The daily scrum meeting is not used as a problem-solving or issue resolution meeting. Issues that are raised are taken offline and usually dealt with by the relevant subgroup immediately after the meeting.

Intro to Scrum in Under 10 Minutes

Can explain XP

The following description was adapted from the XP home page, emphasis added:

Extreme Programming (XP) stresses customer satisfaction. Instead of delivering everything you could possibly want on some date far in the future, this process delivers the software you need as you need it.

XP aims to empower developers to confidently respond to changing customer requirements, even late in the life cycle.

XP emphasizes teamwork. Managers, customers, and developers are all equal partners in a collaborative team. XP implements a simple, yet effective environment enabling teams to become highly productive. The team self-organizes around the problem to solve it as efficiently as possible.

XP aims to improve a software project in five essential ways: communication, simplicity, feedback, respect, and courage. Extreme Programmers constantly communicate with their customers and fellow programmers. They keep their design simple and clean. They get feedback by testing their software starting on day one. Every small success deepens their respect for the unique contributions of each and every team member. With this foundation, Extreme Programmers are able to courageously respond to changing requirements and technology.

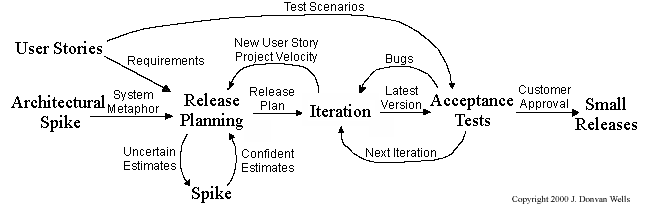

XP has a set of simple rules. XP is a lot like a jig saw puzzle with many small pieces. Individually the pieces make no sense, but when combined together a complete picture can be seen. This flow chart shows how Extreme Programming's rules work together.

Pair programming, CRC cards, project velocity, and standup meetings are some interesting topics related to XP. Refer to extremeprogramming.org to find out more about XP.

Can explain process models at a higher level

This section has some exercises that cover multiple topics related to SDLC process models.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As you will be updating documentation of your project soon, here are some guidelines to help you with that.

Type of Developer Docs

Can explain the two types of developer docs

Developer-to-developer documentation can be in one of two forms:

- Documentation for developer-as-user: Software components are written by developers and reused by other developers, which means there is a need to document how such components are to be used. Such documentation can take several forms:

- API documentation: APIs expose functionality in small-sized, independent and easy-to-use chunks, each of which can be documented systematically.

- Tutorial-style instructional documentation: In addition to explaining functions/methods independently, some higher-level explanations of how to use an API can be useful.

- Example of API Documentation: String API.

- Example of tutorial-style documentation: Java Internationalization Tutorial.

- Example of API Documentation: string API.

- Example of tutorial-style documentation: How to use Regular Expressions in Python

- Documentation for developer-as-maintainer: There is a need to document how a system or a component is designed, implemented and tested so that other developers can maintain and evolve the code. Writing documentation of this type is harder because of the need to explain complex internal details. However, given that readers of this type of documentation usually have access to the source code itself, only some information needs to be included in the documentation, as code (and code comments) can also serve as a complementary source of information.

- An example: se-edu/addressbook-level4 Developer Guide.

Another view proposed by Daniele Procida in this article is as follows:

There is a secret that needs to be understood in order to write good software documentation: there isn’t one thing called documentation, there are four. They are: tutorials, how-to guides, explanation and technical reference. They represent four different purposes or functions, and require four different approaches to their creation. Understanding the implications of this will help improve most software documentation - often immensely. ...

TUTORIALS

A tutorial:

- is learning-oriented

- allows the newcomer to get started

- is a lesson

Analogy: teaching a small child how to cook

HOW-TO GUIDES

A how-to guide:

- is goal-oriented

- shows how to solve a specific problem

- is a series of steps

Analogy: a recipe in a cookery book

EXPLANATION

An explanation:

- is understanding-oriented

- explains

- provides background and context

Analogy: an article on culinary social history

REFERENCE

A reference guide:

- is information-oriented

- describes the machinery

- is accurate and complete

Analogy: a reference encyclopedia article

Software documentation (applies to both user-facing and developer-facing) is best kept in a text format for ease of version tracking. A writer-friendly source format is also desirable as non-programmers (e.g., technical writers) may need to author/edit such documents. As a result, formats such as Markdown, AsciiDoc, and PlantUML are often used for software documentation.

Guideline: Aim for Comprehensibility

Can explain the need for comprehensibility in documents

Technical documents exist to help others understand technical details. Therefore, it is not enough for the documentation to be accurate and comprehensive; it should also be comprehensible.

Can write reasonably comprehensible developer documents

Here are some tips on writing effective documentation.

- Use plenty of diagrams: It is not enough to explain something in words; complement it with visual illustrations (e.g. a UML diagram).

- Use plenty of examples: When explaining algorithms, show a running example to illustrate each step of the algorithm, in parallel to worded explanations.

- Use simple and direct explanations: Convoluted explanations and fancy words will annoy readers. Avoid long sentences.

- Get rid of statements that do not add value: For example, 'We made sure our system works perfectly' (who didn't?), 'Component X has its own responsibilities' (of course it has!).

- It is not a good idea to have separate sections for each type of artifact, such as 'use cases', 'sequence diagrams', 'activity diagrams', etc. Such a structure, coupled with the indiscriminate inclusion of diagrams without justifying their need, indicates a failure to understand the purpose of documentation. Include diagrams when they are needed to explain something. If you want to provide additional diagrams for completeness' sake, include them in the appendix as a reference.

Guideline: Describe Top-Down

Can explain the advantages of top-down documentation

The main advantage of the top-down approach is that the document is structured like an upside down tree (root at the top) and the reader can travel down a path she is interested in until she reaches the component she is interested to learn in-depth, without having to read the entire document or understand the whole system.

Can write documentation in a top-down manner

To explain a system called SystemFoo with two sub-systems, FrontEnd and BackEnd, start by describing the system at the highest level of abstraction, and progressively drill down to lower level details. An outline for such a description is given below.

[First, explain what the system is, in a black-box fashion (no internal details, only the external view).]

SystemFoois a ....

[Next, explain the high-level architecture of SystemFoo, referring to its major components only.]

SystemFooconsists of two major components:FrontEndandBackEnd.

The job ofFrontEndis to ... while the job ofBackEndis to ...

And this is howFrontEndandBackEndwork together ...

[Now you can drill down to FrontEnd's details.]

FrontEndconsists of three major components:A,B,C

A's job is to ...B's job is to...C's job is to...

And this is how the three components work together ...

[At this point, further drill down to the internal workings of each component. A reader who is not interested in knowing the nitty-gritty details can skip ahead to the section on BackEnd.]

In-depth description of

A

In-depth description ofB

...

[At this point drill down to the details of the BackEnd.]

...

Guideline: Minimal but Sufficient

Can explain that documentation should be minimal yet sufficient

Aim for 'just enough' developer documentation.

- Writing and maintaining developer documents is an overhead. You should try to minimize that overhead.

- If the readers are developers who will eventually read the code, the documentation should complement the code and should provide only just enough guidance to get started.

Can write minimal yet sufficient documentation

Anything that is already clear in the code need not be described in words. Instead, focus on providing higher level information that is not readily visible in the code or comments.

Refrain from duplicating chunks of text. When describing several similar algorithms/designs/APIs, etc., do not simply duplicate large chunks of text. Instead, describe the similarities in one place and emphasize only the differences in other places. It is very annoying to see pages and pages of similar text without any indication as to how they differ from each other.