Week 3 [Fri, Aug 25th] - Topics

Detailed Table of Contents

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Let's learn about a few more Git techniques, starting with branching. Although these techniques are not really needed for the iP, we require you to use them in the iP so that you have more time to practice them before they are really needed in the tP.

Can explain branching

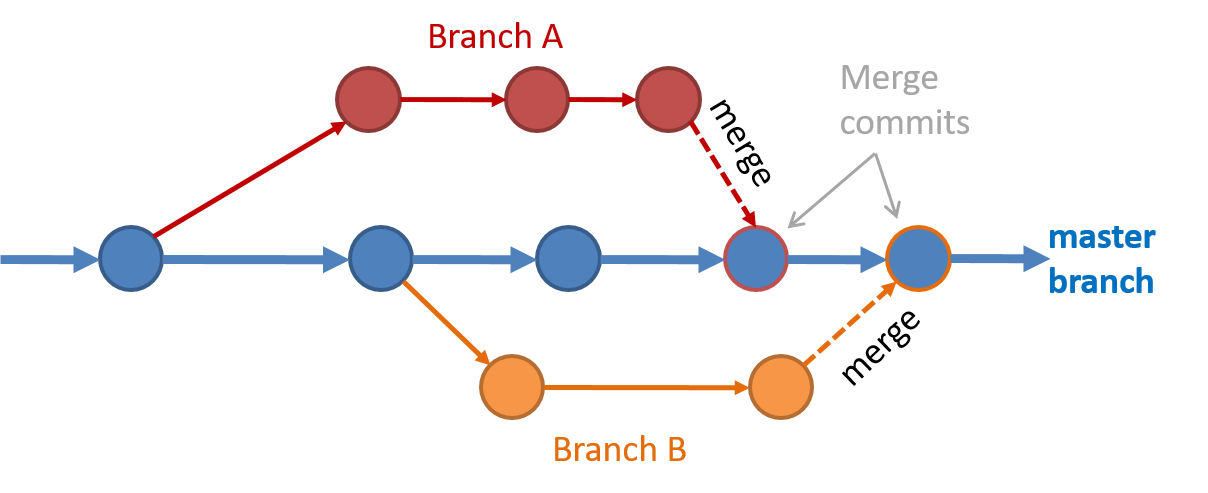

Branching is the process of evolving multiple versions of the software in parallel. For example, one team member can create a new branch and add an experimental feature to it while the rest of the team keeps working on another branch. Branches can be given names e.g. master, release, dev.

A branch can be merged into another branch. Merging usually results in a new commit that represents the changes done in the branch being merged.

Branching and merging

Branching and merging Merge conflicts happen when you try to merge two branches that had changed the same part of the code and the RCS cannot decide which changes to keep. In those cases, you have to ‘resolve’ the conflicts manually.

Can use Git branching

Git supports branching, which allows you to do multiple parallel changes to the content of a repository.

First, let us learn how the repo looks like as you perform branching operations.

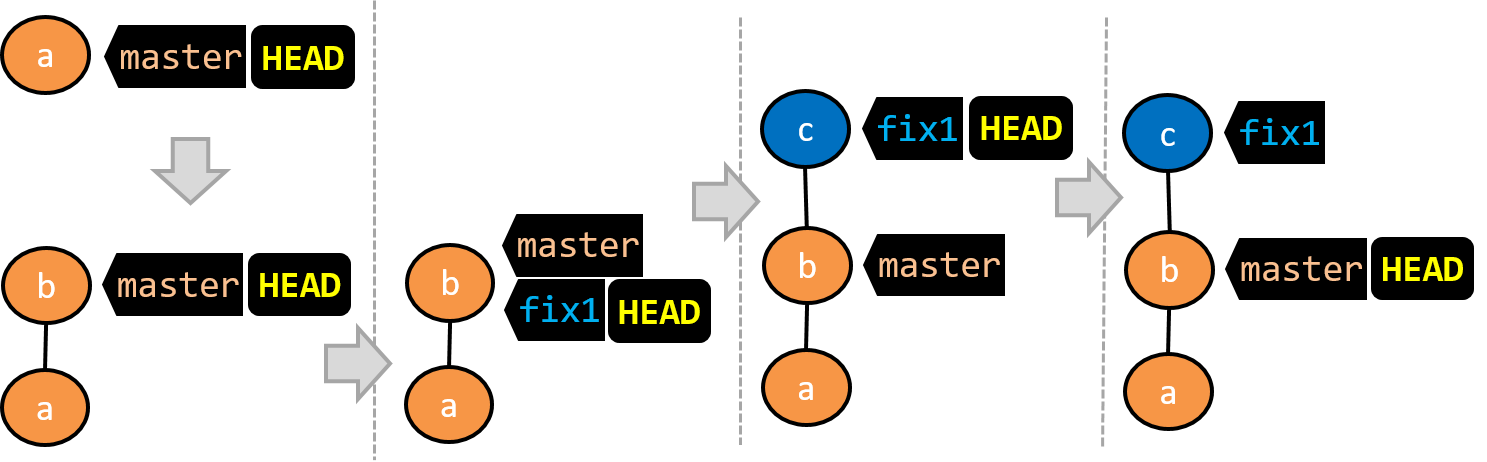

A Git branch is simply a named label pointing to a commit. The HEAD label indicates which branch you are on. Git creates a branch named master by default. When you add a commit, it goes into the branch you are currently on, and the branch label (together with the HEAD label) moves to the new commit.

Given below is an illustration of how branch labels move as branches evolve. Refer to the text below it for explanations of each stage.

There is only one branch (i.e.,

master) and there is only one commit on it. TheHEADlabel is pointing to themasterbranch (as we are currently on that branch).To learn a bit more about how labels such as

masterandHEADwork, you can refer to this article.A new commit has been added. The

masterand theHEADlabels have moved to the new commit.A new branch

fix1has been added. The repo has switched to the new branch too (hence, theHEADlabel is attached to thefix1branch).A new commit (

c) has been added. The current branch labelfix1moves to the new commit, together with theHEADlabel.The repo has switched back to the

masterbranch. Hence, theHEADhas moved back tomasterbranch's .

At this point, the repo's working directory reflects the code at commitb(notc).

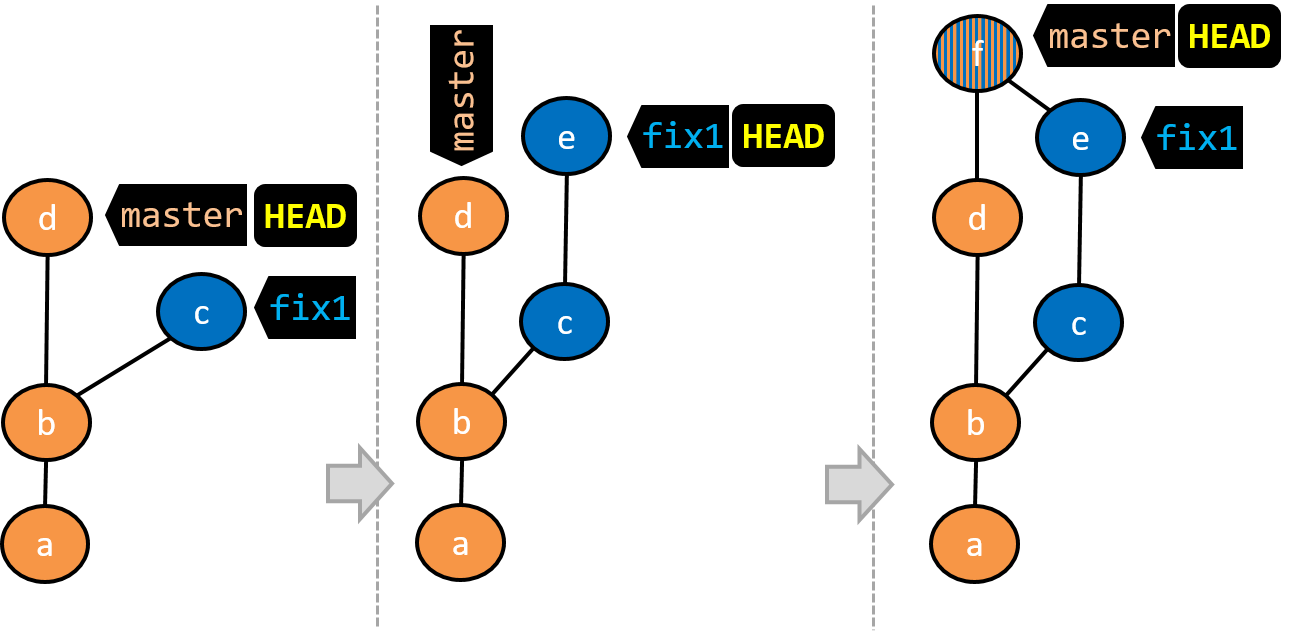

- A new commit (

d) has been added. Themasterand theHEADlabels have moved to that commit. - The repo has switched back to the

fix1branch and added a new commit (e) to it. - The repo has switched to the

masterbranch and thefix1branch has been merged into themasterbranch, creating a merge commitf. The repo is currently on themasterbranch.

Now that you have some idea how the repo will look like when branches are being used, let's follow the steps below to learn how to perform branching operations using Git. You can use any repo you have on your computer (e.g. a clone of the samplerepo-things) for this.

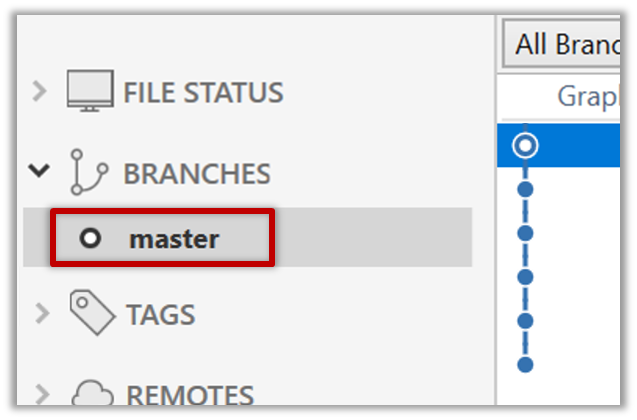

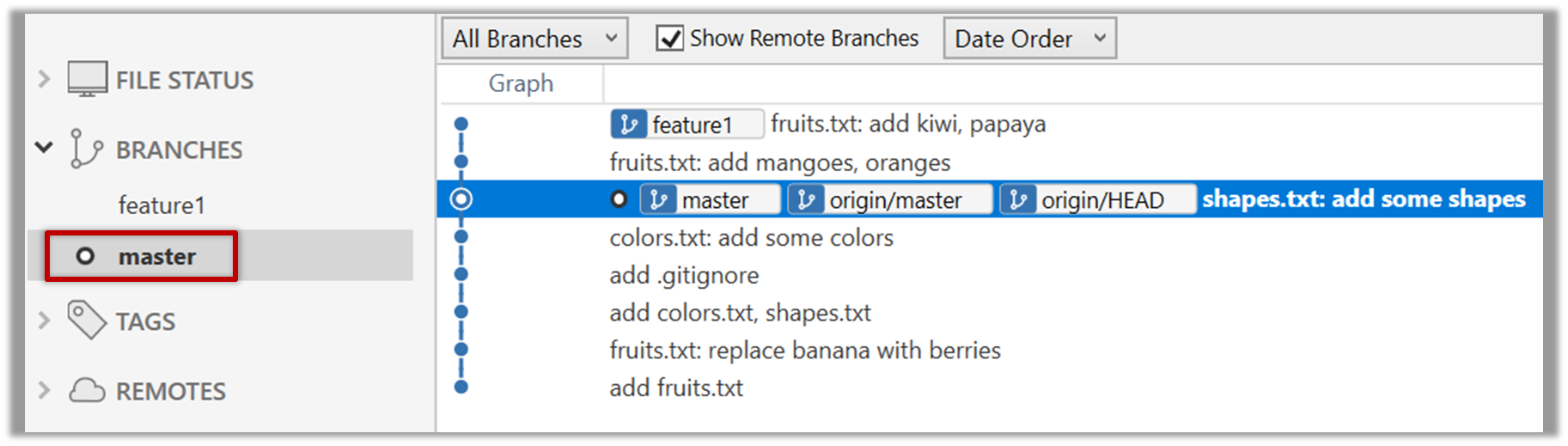

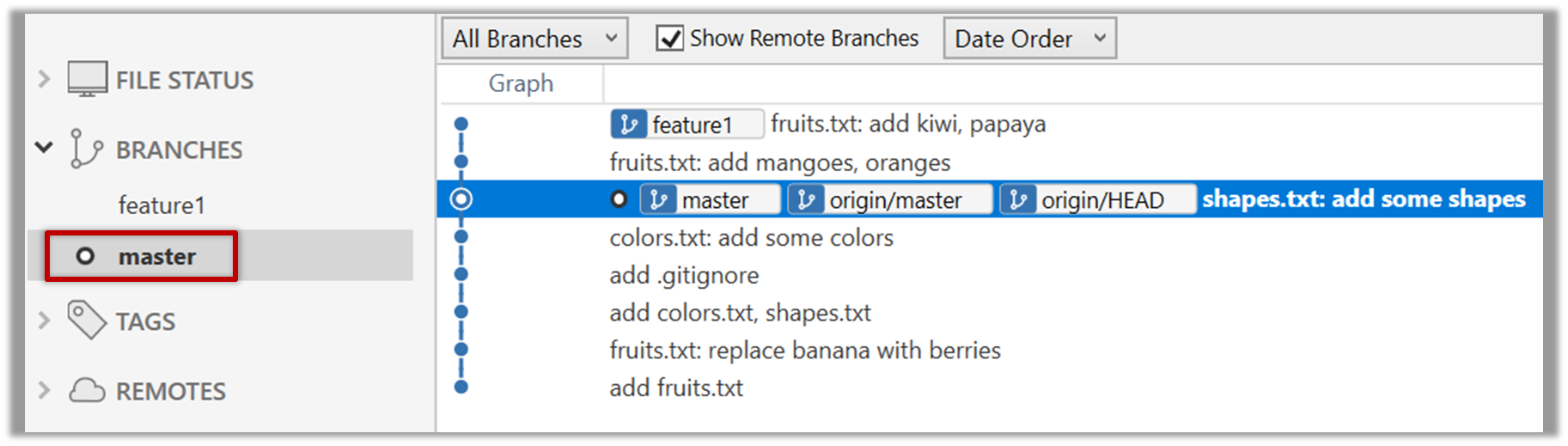

0. Observe that you are normally in the branch called master.

$ git status

on branch master

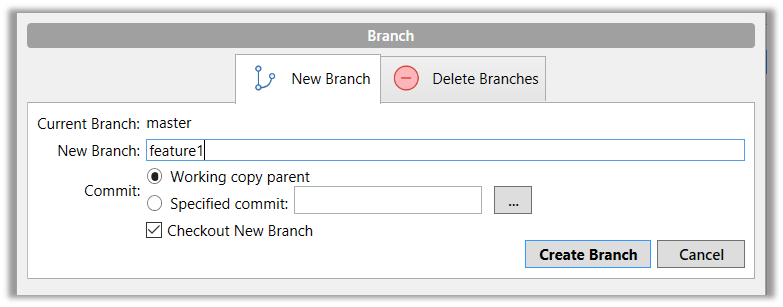

1. Start a branch named feature1 and switch to the new branch.

Click on the Branch button on the main menu. In the next dialog, enter the branch name and click Create Branch.

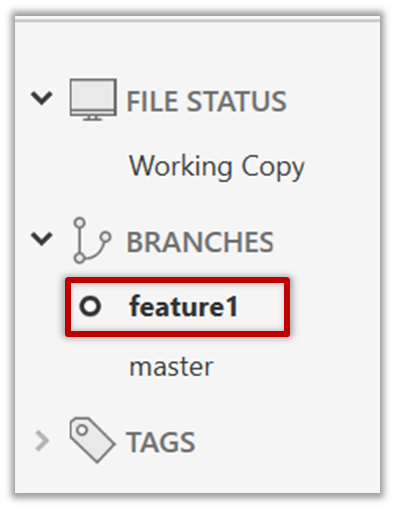

Note how the feature1 is indicated as the current branch (reason: Sourcetree automatically switches to the new branch when you create a new branch).

You can use the branch command to create a new branch and the checkout command to switch to a specific branch.

$ git branch feature1

$ git checkout feature1

One-step shortcut to create a branch and switch to it at the same time:

$ git checkout –b feature1

2. Create some commits in the new branch. Just commit as per normal. Commits you add while on a certain branch will become part of that branch.

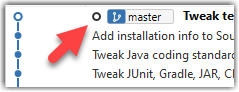

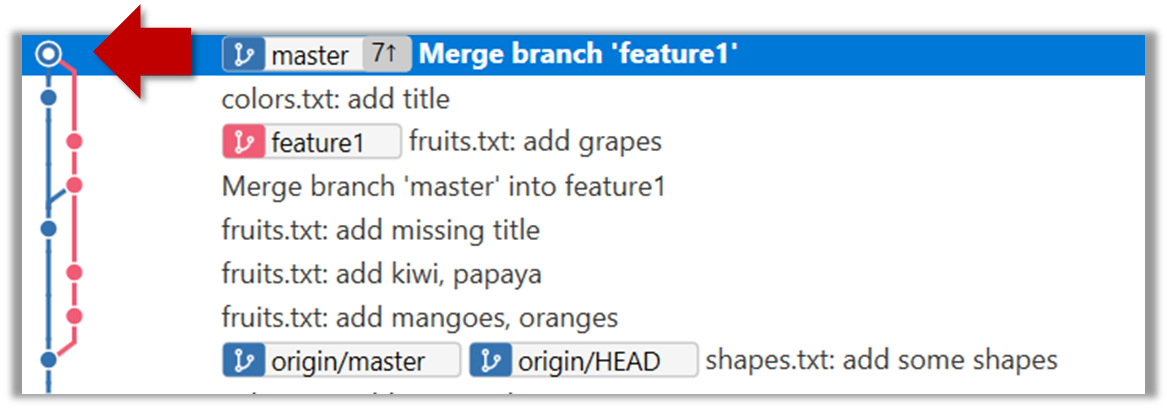

Note how the master label and the HEAD label moves to the new commit (The HEAD label of the local repo is represented as in Sourcetree).

3. Switch to the master branch. Note how the changes you did in the feature1 branch are no longer in the working directory.

Double-click the master branch.

$ git checkout master

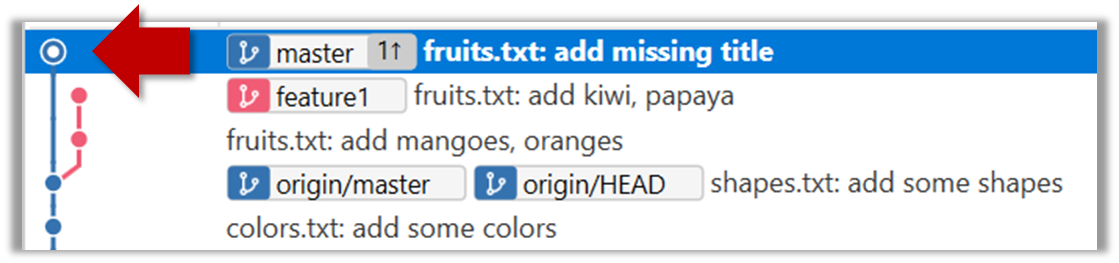

4. Add a commit to the master branch. Let’s imagine it’s a bug fix.

To keep things simple for the time being, this commit should not involve the same content that you changed in the feature1 branch. To be on the safe side, you can change an entirely different file in this commit.

5. Switch back to the feature1 branch (similar to step 3).

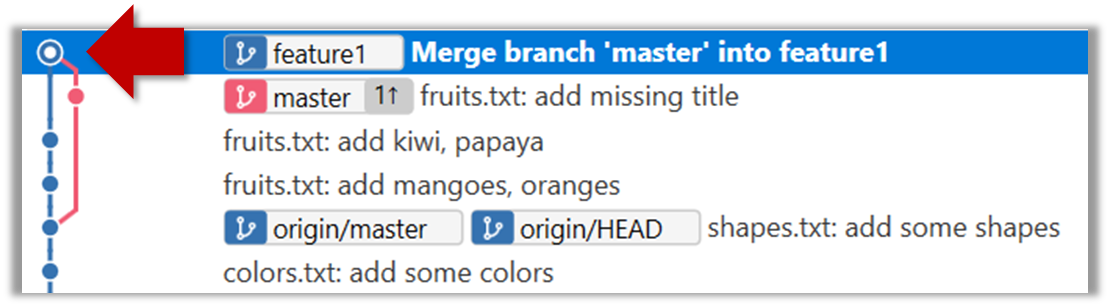

6. Merge the master branch to the feature1 branch, giving an end-result like the following. Also note how Git has created a merge commit.

Right-click on the master branch and choose merge master into the current branch. Click OK in the next dialog.

$ git merge master

The objective of that merge was to sync the feature1 branch with the master branch. Observe how the changes you did in the master branch (i.e. the imaginary bug fix) is now available even when you are in the feature1 branch.

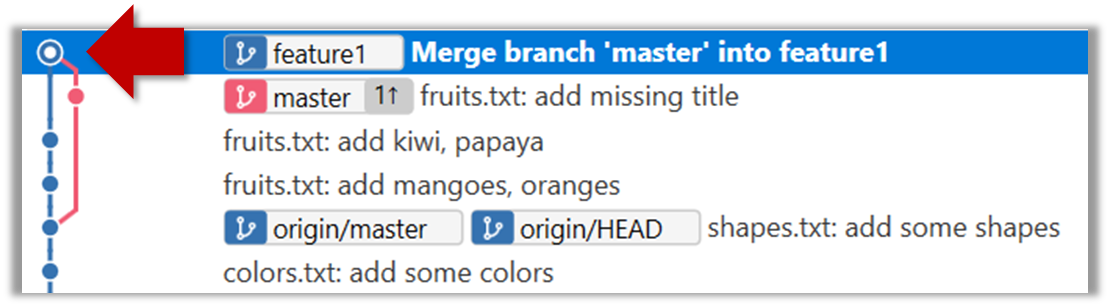

To undo a merge,

- Ensure you are in the branch that received the merge.

- Do a hard reset (similar to how you delete a commit) of that branch to the commit that would be the tip of that branch had you not done the offending merge.

In the example below, you merged master to feature1.

If you want to undo that merge,

- Ensure you are in the

feature1branch. - Reset the

feature1branch to the commit highlighted in the screenshot above (because that was the tip of thefeature1branch before you merged themasterbranch to it.

Instead of merging master to feature1, an alternative is to rebase the feature1 branch. However, rebasing is an advanced feature that requires modifying past commits. If you modify past commits that have been pushed to a remote repository, you'll have to force-push the modified commit to the remote repo in order to update the commits in it.

7. Add another commit to the feature1 branch.

8. Switch to the master branch and add one more commit.

9. Merge feature1 to the master branch, giving and end-result like this:

Right-click on the feature1 branch and choose Merge....

$ git merge feature1

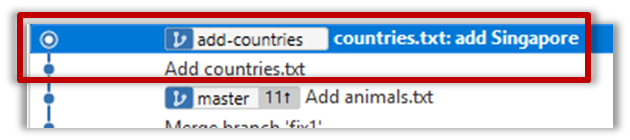

10. Create a new branch called add-countries, switch to it, and add some commits to it (similar to steps 1-2 above). You should have something like this now:

Avoid this common rookie mistake!

Always remember to switch back to the master branch before creating a new branch. If not, your new branch will be created on top of the current branch.

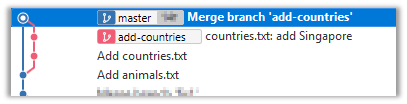

11. Go back to the master branch and merge the add-countries branch onto the master branch (similar to steps 8-9 above). While you might expect to see something like the following,

... you are likely to see something like this instead:

That is because Git does a fast forward merge if possible. Seeing that the master branch has not changed since you started the add-countries branch, Git has decided it is simpler to just put the commits of the add-countries branch in front of the master branch, without going into the trouble of creating an extra merge commit.

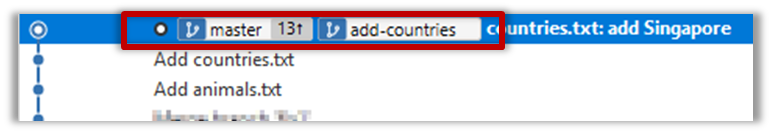

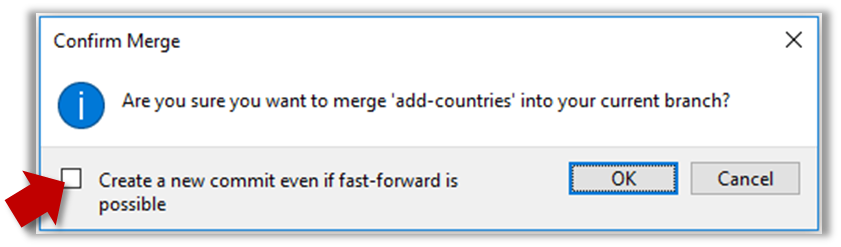

It is possible to force Git to create a merge commit even if fast forwarding is possible.

Tick the box shown below when you merge a branch:

Use the --no-ff switch (short for no fast forward):

$ git merge --no-ff add-countries

Can use Git to resolve merge conflicts

Merge conflicts happen when you try to combine two incompatible versions (e.g., merging a branch to another but each branch changed the same part of the code in a different way).

Here are the steps to simulate a merge conflict and use it to learn how to resolve merge conflicts.

0. Create an empty repo or clone an existing repo, to be used for this activity.

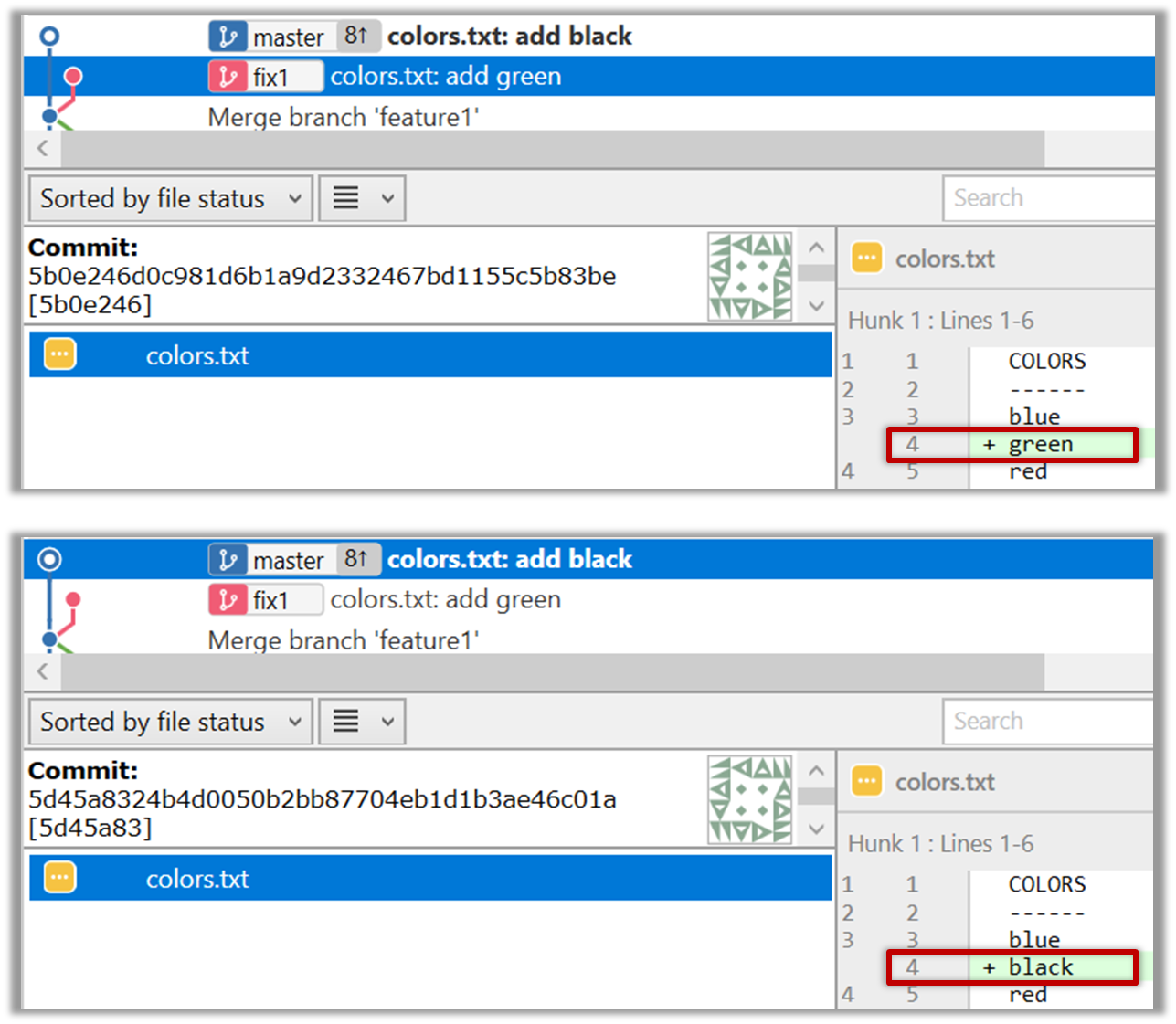

1. Start a branch named fix1 in the repo. Create a commit that adds a line with some text to one of the files.

2. Switch back to master branch. Create a commit with a conflicting change i.e. it adds a line with some different text in the exact location the previous line was added.

3. Try to merge the fix1 branch onto the master branch. Git will pause mid-way during the merge and report a merge conflict. If you open the conflicted file, you will see something like this:

COLORS

------

blue

<<<<<< HEAD

black

=======

green

>>>>>> fix1

red

white

4. Observe how the conflicted part is marked between a line starting with <<<<<< and a line starting with >>>>>>, separated by another line starting with =======.

Highlighted below is the conflicting part that is coming from the master branch:

blue

<<<<<< HEAD

black

=======

green

>>>>>> fix1

red

This is the conflicting part that is coming from the fix1 branch:

blue

<<<<<< HEAD

black

=======

green

>>>>>> fix1

red

5. Resolve the conflict by editing the file. Let us assume you want to keep both lines in the merged version. You can modify the file to be like this:

COLORS

------

blue

black

green

red

white

6. Stage the changes, and commit. You have now successfully resolved the merge conflict.

Can work with remote branches

Git branches in a local repo can be linked to a branch in a remote repo so the local branch can 'track' the corresponding remote branch, and revision history contained in the local and the remote branch pair can be synchronized as desired.

[A] Pushing a new branch to a remote repo

Let's see how you can push a branch that you created in your local repo to the remote repo. Note that this branch does not exist in the remote repo yet.

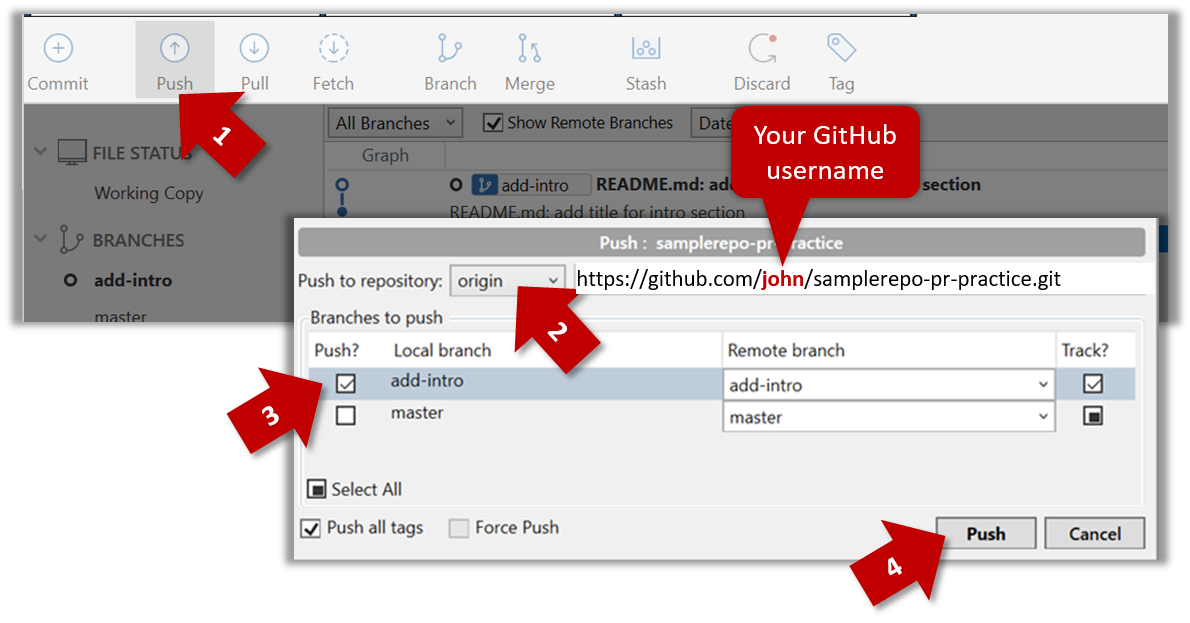

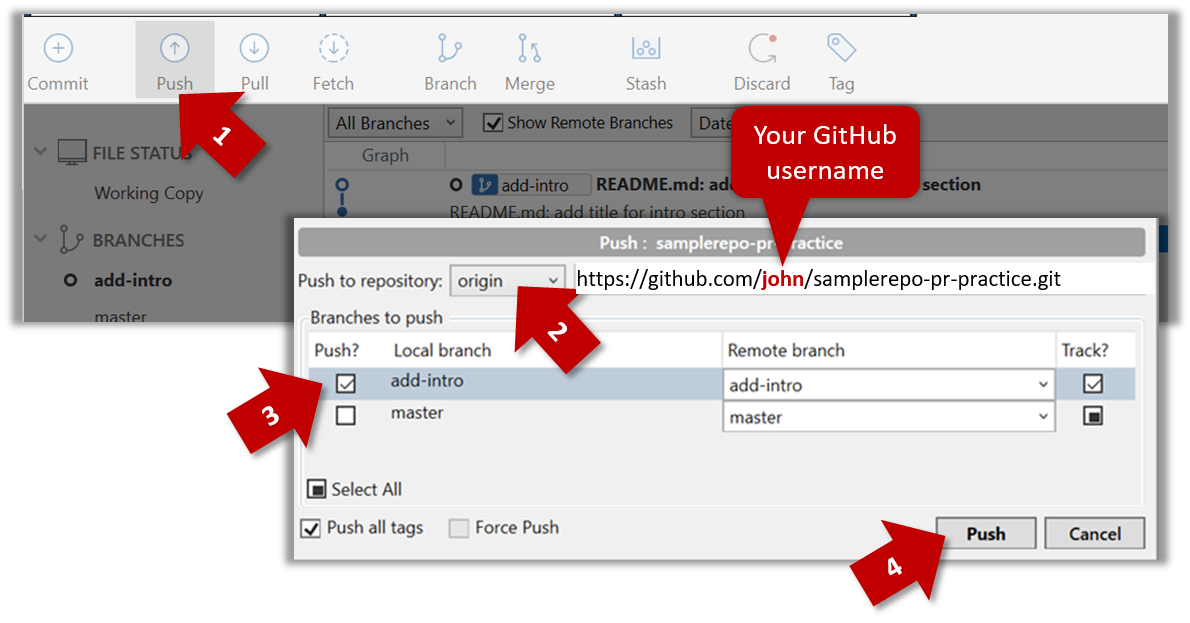

Given below is how to push a branch named add-intro to your own fork named samplerepo-pr-practice.

We assume that your local repo already has the remote added to it with the name origin. If that is not the case, you should first configure your local repo to be able to communicate with the target remote repo.

- Click on

Pushbutton, which opens up the Push dialog. - Choose the remote that you wish to push the branch (assuming you've added that repo to your Sourcetree already).

- Select the branch(es) you want to push -- in this case,

add-intro.

Ensure theTrack?checkbox is ticked for the selected branch(es). - Click

Push.

$ git push -u origin add-intro

The -u (or --update) flag tells Git that you wish the local branch to 'track' the remote branch that will be created as a result of this push.

See git-scm.com/docs/git-push for details of the push command.

[B] Pulling a remote branch for the first time

Here, let's see how to fetch a new branch (i.e., it does not exist in your local repo yet) from a remote repo.

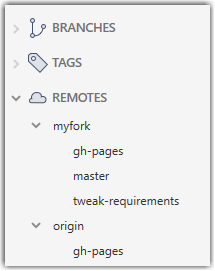

1. Check the list of remote branches by expanding the REMOTES menu on the left edge of Sourcetree. If the branch you expected to find is missing, you can click the Fetch button (in the top toolbar) to refresh the information shown under remotes.

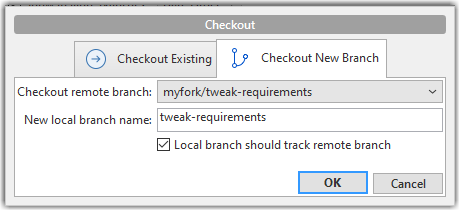

2. Double-click the branch name (e.g., tweak-requirements branch in the myfork remote), which should open the checkout dialog shown below.

3. Go with the default settings (shown above) should be fine. Once you click OK, the branch will appear in your local repo. Furthermore, that repo will switch to that branch, and the local branch will the remote branch as well.

1. Fetch details from the remote. e.g., if the remote is named myfork

$ git fetch myfork

2. List the branches to see the name of the branch you want to pull.

$ git branch -a

master

remotes/myfork/master

remotes/myfork/branch1

-a flag tells Git to list both local and remote branches.

3. Create a matching local branch and switch to it.

$ git switch -c branch1 myfork/branch1

Switched to a new branch 'branch1'

branch 'branch1' set up to track 'myfork/branch1'.

-c flag tells Git to create a new local branch.

[C] Syncing branches

In this section we assume that you have a local branch that is already tracking a remote branch (e.g., as a result of doing [A] or [B] above).

To push new changes in the local branch to the corresponding remote branch:

Similar to how you pushed a new branch (in [A]):

Similar to [A] above, but omit the -u flag. e.g.,

$ git push origin add-intro

If you push but the remote branch has new commits that you don't have locally, Git will abort the push and will ask you to pull first.

To pull new changes from a remote branch to the corresponding local branch:

1. Switch to the branch you want to update by double-clicking the branch name. e.g.,

2. Pull the updated in the remote branch to the local branch by right-clicking on the branch name (in the same place as above), and choosing Pull <remote>/<branch> (tracked) e.g., Pull myfork/add-intro (tracked).

1. Switch to the branch you want to update using git checkout <branch> e.g.,

$ git checkout branch1

2. Pull the updated in the remote branch to the local branch, using git pull <remote> <branch> e.g.,

$ git pull origin branch1

If you pull but your local branch has new commits the remote branch doesn't have, Git will automatically perform a merge between the local branch and the remote branch.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Let's learn how to create a pull request (PRs) on GitHub; you need to create one for your project this week.

Can create PRs on GitHub

Suppose you want to propose some changes to a GitHub repo (e.g., samplerepo-pr-practice) as a pull request (PR).

samplerepo-pr-practice is an unmonitored repo you can use to practice working with PRs. Feel free to send PRs to it.

Given below is a scenario you can try in order to learn how to create PRs:

1. Fork the repo onto your GitHub account.

2. Clone it onto your computer.

3. Commit your changes e.g., add a new file with some contents and commit it.

- Option A - Commit changes to the

masterbranch - Option B - Commit to a new branch e.g., create a branch named

add-intro(remember to switch to themasterbranch before creating a new branch) and add your commit to it.

4. Push the branch you updated (i.e., master branch or the new branch) to your fork, as explained here.

5. Initiate the PR creation:

Go to your fork.

Click on the Pull requests tab followed by the New pull request button. This will bring you to the

Compare changespage.Set the appropriate target repo and the branch that should receive your PR, using the

base repositoryandbasedropdowns. e.g.,

base repository: se-edu/samplerepo-pr-practice base: masterNormally, the default value shown in the dropdown is what you want but in case your fork has , the default may not be what you want.

Indicate which repo:branch contains your proposed code, using the

head repositoryandcomparedropdowns. e.g.,

head repository: myrepo/samplerepo-pr-practice compare: master

6. Verify the proposed code: Verify that the diff view in the page shows the exact change you intend to propose. If it doesn't, as necessary.

7. Submit the PR:

Click the Create pull request button.

Fill in the PR name and description e.g.,

Name:Add an introduction to the README.md

Description:Add some paragraph to the README.md to explain ... Also add a heading ...If you want to indicate that the PR you are about to create is 'still work in progress, not yet ready', click on the dropdown arrow in the Create pull request button and choose

Create draft pull requestoption.Click the Create pull request button to create the PR.

Go to the receiving repo to verify that your PR appears there in the

Pull requeststab.

The next step of the PR life cycle is the PR review. The members of the repo that received your PR can now review your proposed changes.

- If they like the changes, they can merge the changes to their repo, which also closes the PR automatically.

- If they don't like it at all, they can simply close the PR too i.e., they reject your proposed change.

- In most cases, they will add comments to the PR to suggest further changes. When that happens, GitHub will notify you.

You can update the PR along the way too. Suppose PR reviewers suggested a certain improvement to your proposed code. To update your PR as per the suggestion, you can simply modify the code in your local repo, commit the updated code to the same branch as before, and push to your fork as you did earlier. The PR will auto-update accordingly.

Sending PRs using the master branch is less common than sending PRs using separate branches. For example, suppose you wanted to propose two bug fixes that are not related to each other. In that case, it is more appropriate to send two separate PRs so that each fix can be reviewed, refined, and merged independently. But if you send PRs using the master branch only, both fixes (and any other change you do in the master branch) will appear in the PRs you create from it.

To create another PR while the current PR is still under review, create a new branch (remember to switch back to the master branch first), add your new proposed change in that branch, and create a new PR following the steps given above.

It is possible to create PRs within the same repo e.g., you can create a PR from branch feature-x to the master branch, within the same repo. Doing so will allow the code to be reviewed by other developers (using PR review mechanism) before it is merged.

Problem: merge conflicts in ongoing PRs, indicated by the message This branch has conflicts that must be resolved. That means the upstream repo's master branch has been updated in a way that the PR code conflicts with that master branch. Here is the standard way to fix this problem:

- Pull the

masterbranch from the upstream repo to your local repo.git checkout master git pull upstream master - In the local repo, and attempt to merge the

masterbranch (that you updated in the previous step) onto the PR branch, in order to bring over the new code in themasterbranch to your PR branch.git checkout pr-branch # assuming pr-branch is the name of branch in the PR git merge master - The merge you are attempting will run into a merge conflict, due to the aforementioned conflicting code in the

masterbranch. Resolve the conflict manually (this topic is covered elsewhere), and complete the merge. - Push the PR branch to your fork. As the updated code in that branch no longer is conflicting with the

masterbranch, the merge conflict alert in the PR will go away automatically.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As your project gets bigger and changes become more frequent, it's natural to look for ways to automate the many steps involved in going from the code you write in the editor to an executable product. This is a good time to start learning about that aspect too.

Can explain build automation tools

Build automation tools automate the steps of the build process, usually by means of build scripts.

In a non-trivial project, building a product from its source code can be a complex multi-step process. For example, it can include steps such as: pull code from the revision control system, compile, link, run automated tests, automatically update release documents (e.g. build number), package into a distributable, push to repo, deploy to a server, delete temporary files created during building/testing, email developers of the new build, and so on. Furthermore, this build process can be done ‘on demand’, it can be scheduled (e.g. every day at midnight) or it can be triggered by various events (e.g. triggered by a code push to the revision control system).

Some of these build steps such as compiling, linking and packaging, are already automated in most modern IDEs. For example, several steps happen automatically when the ‘build’ button of the IDE is clicked. Some IDEs even allow customization of this build process to some extent.

However, most big projects use specialized build tools to automate complex build processes.

Some popular build tools relevant to Java developers: Gradle, Maven, Apache Ant, GNU Make

Some other build tools: Grunt (JavaScript), Rake (Ruby)

Some build tools also serve as dependency management tools. Modern software projects often depend on third party libraries that evolve constantly. That means developers need to download the correct version of the required libraries and update them regularly. Therefore, dependency management is an important part of build automation. Dependency management tools can automate that aspect of a project.

Maven and Gradle, in addition to managing the build process, can play the role of dependency management tools too.

Can explain continuous integration and continuous deployment

An extreme application of build automation is called continuous integration (CI) in which integration, building, and testing happens automatically after each code change.

A natural extension of CI is Continuous Deployment (CD) where the changes are not only integrated continuously, but also deployed to end-users at the same time.

Some examples of CI/CD tools: Travis, Jenkins, Appveyor, CircleCI, GitHub Actions

Guidance for the item(s) below:

Next, we have a few more Java topics that you need as you move from a 'programming exercise' mode to a 'production code' mode.

Can explain JavaDoc

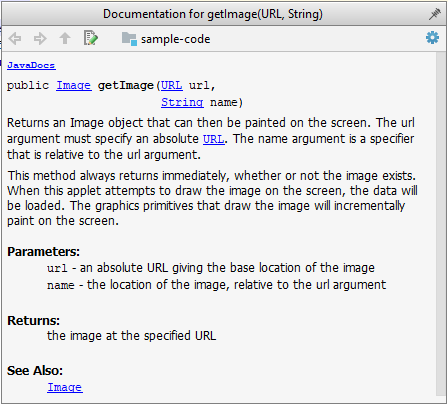

JavaDoc is a tool for generating API documentation in HTML format from comments in the source code. In addition, modern IDEs use JavaDoc comments to generate explanatory tooltips.

An example method header comment in JavaDoc format:

/**

* Returns an Image object that can then be painted on the screen.

* The url argument must specify an absolute {@link URL}. The name

* argument is a specifier that is relative to the url argument.

* <p>

* This method always returns immediately, whether or not the

* image exists. When this applet attempts to draw the image on

* the screen, the data will be loaded. The graphics primitives

* that draw the image will incrementally paint on the screen.

*

* @param url an absolute URL giving the base location of the image

* @param name the location of the image, relative to the url argument

* @return the image at the specified URL

* @see Image

*/

public Image getImage(URL url, String name) {

try {

return getImage(new URL(url, name));

} catch (MalformedURLException e) {

return null;

}

}

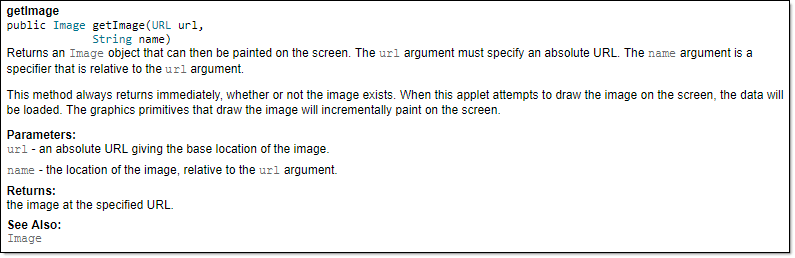

Generated HTML documentation:

Tooltip generated by IntelliJ IDE:

Can write JavaDoc comments

In the absence of more extensive guidelines (e.g., given in a coding standard adopted by your project), you can follow the two examples below in your code.

A minimal JavaDoc comment example for methods:

/**

* Returns lateral location of the specified position.

* If the position is unset, NaN is returned.

*

* @param x X coordinate of position.

* @param y Y coordinate of position.

* @param zone Zone of position.

* @return Lateral location.

* @throws IllegalArgumentException If zone is <= 0.

*/

public double computeLocation(double x, double y, int zone)

throws IllegalArgumentException {

// ...

}

A minimal JavaDoc comment example for classes:

package ...

import ...

/**

* Represents a location in a 2D space. A <code>Point</code> object corresponds to

* a coordinate represented by two integers e.g., <code>3,6</code>

*/

public class Point {

// ...

}

Resources:

- A short tutorial on writing JavaDoc comments -- from tutorialspoint.com

- A more detailed description -- from Oracle

Can read/write text files using Java

You can use the java.io.File class to represent a file object. It can be used to access properties of the file object.

This code creates a File object to represent a file fruits.txt that exists in the data directory relative to the current working directory and uses that object to print some properties of the file.

import java.io.File;

public class FileClassDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

File f = new File("data/fruits.txt");

System.out.println("full path: " + f.getAbsolutePath());

System.out.println("file exists?: " + f.exists());

System.out.println("is Directory?: " + f.isDirectory());

}

}

full path: C:\sample-code\data\fruits.txt

file exists?: true

is Directory?: false

If you use backslash to specify the file path in a Windows computer, you need to use an additional backslash as an escape character because the backslash by itself has a special meaning. e.g., use "data\\fruits.txt", not "data\fruits.txt". Alternatively, you can use forward slash "data/fruits.txt" (even on Windows).

You can read from a file using a Scanner object that uses a File object as the source of data.

This code uses a Scanner object to read (and print) contents of a text file line-by-line:

import java.io.File;

import java.io.FileNotFoundException;

import java.util.Scanner;

public class FileReadingDemo {

private static void printFileContents(String filePath) throws FileNotFoundException {

File f = new File(filePath); // create a File for the given file path

Scanner s = new Scanner(f); // create a Scanner using the File as the source

while (s.hasNext()) {

System.out.println(s.nextLine());

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

try {

printFileContents("data/fruits.txt");

} catch (FileNotFoundException e) {

System.out.println("File not found");

}

}

}

i.e., contents of the data/fruits.txt

5 Apples

3 Bananas

6 Cherries

You can use a java.io.FileWriter object to write to a file.

The writeToFile method below uses a FileWrite object to write to a file. The method is being used to write two lines to the file temp/lines.txt.

import java.io.FileWriter;

import java.io.IOException;

public class FileWritingDemo {

private static void writeToFile(String filePath, String textToAdd) throws IOException {

FileWriter fw = new FileWriter(filePath);

fw.write(textToAdd);

fw.close();

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

String file2 = "temp/lines.txt";

try {

writeToFile(file2, "first line" + System.lineSeparator() + "second line");

} catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println("Something went wrong: " + e.getMessage());

}

}

}

Contents of the temp/lines.txt:

first line

second line

Note that you need to call the close() method of the FileWriter object for the writing operation to be completed.

You can create a FileWriter object that appends to the file (instead of overwriting the current content) by specifying an additional boolean parameter to the constructor.

The method below appends to the file rather than overwrites.

private static void appendToFile(String filePath, String textToAppend) throws IOException {

FileWriter fw = new FileWriter(filePath, true); // create a FileWriter in append mode

fw.write(textToAppend);

fw.close();

}

The java.nio.file.Files is a utility class that provides several useful file operations. It relies on the java.nio.file.Paths file to generate Path objects that represent file paths.

This example uses the Files class to copy a file and delete a file.

import java.io.IOException;

import java.nio.file.Files;

import java.nio.file.Paths;

public class FilesClassDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException{

Files.copy(Paths.get("data/fruits.txt"), Paths.get("temp/fruits2.txt"));

Files.delete(Paths.get("temp/fruits2.txt"));

}

}

The techniques above are good enough to manipulate simple text files. Note that it is also possible to perform file I/O operations using other classes.

Can use Java packages

You can organize your types (i.e., classes, interfaces, enumerations, etc.) into packages for easier management (among other benefits).

To create a package, you put a package statement at the very top of every source file in that package. The package statement must be the first line in the source file and there can be no more than one package statement in each source file. Furthermore, the package of a type should match the folder path of the source file. Similarly, the compiler will put the .class files in a folder structure that matches the package names.

The Formatter class below (in <source folder>/seedu/tojava/util/Formatter.java file) is in the package seedu.tojava.util. When it is compiled, the Formatter.class file will be in the location <compiler output folder>/seedu/tojava/util:

package seedu.tojava.util;

public class Formatter {

public static final String PREFIX = ">>";

public static String format(String s){

return PREFIX + s;

}

}

Package names are written in all lower case (not camelCase), using the dot as a separator. Packages in the Java language itself begin with java. or javax. Companies use their reversed Internet domain name to begin their package names.

For example, com.foobar.doohickey.util can be the name of a package created by a company with a domain name foobar.com

To use a public from outside its package, you must do one of the following:

- Use the to refer to the member

- Import the package or the specific package member

The Main class below has two import statements:

import seedu.tojava.util.StringParser: imports the classStringParserin theseedu.tojava.utilpackageimport seedu.tojava.frontend.*: imports all the classes in theseedu.tojava.frontendpackage

package seedu.tojava;

import seedu.tojava.util.StringParser;

import seedu.tojava.frontend.*;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Using the fully qualified name to access the Processor class

String status = seedu.tojava.logic.Processor.getStatus();

// Using the StringParser previously imported

StringParser sp = new StringParser();

// Using classes from the tojava.frontend package

Ui ui = new Ui();

Message m = new Message();

}

}

Note how the class can still use the Processor without importing it first, by using its fully qualified name seedu.tojava.logic.Processor

Importing a package does not import its sub-packages, as packages do not behave as hierarchies despite appearances.

import seedu.tojava.frontend.* does not import the classes in the sub-package seedu.tojava.frontend.widget.

If you do not use a package statement, your type doesn't have a package -- a practice not recommended (except for small code examples) as it is not possible for a type in a package to import a type that is not in a package.

Optionally, a static import can be used to import static members of a type so that the imported members can be used without specifying the type name.

The class below uses static imports to import the constant PREFIX and the method format() from the seedu.tojava.util.Formatter class.

import static seedu.tojava.util.Formatter.PREFIX;

import static seedu.tojava.util.Formatter.format;

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

String formatted = format("Hello");

boolean isFormatted = formatted.startsWith(PREFIX);

System.out.println(formatted);

}

}

Formatter class

Note how the class can use PREFIX and format() (instead of Formatter.PREFIX and Formatter.format()).

When using the commandline to compile/run Java, you should take the package into account.

If the seedu.tojava.Main class is defined in the file Main.java,

- when compiling from the

<source folder>, the command is:

javac seedu/tojava/Main.java - when running it from the

<compiler output folder>, the command is:

java seedu.tojava.Main

Can use JAR files

Java applications are typically delivered as JAR (short for Java Archive) files. A JAR contains Java classes and other resources (icons, media files, etc.).

An executable JAR file can be launched using the java -jar command e.g., java -jar foo.jar launches the foo.jar file.

The IDE or build tools such as Gradle can help you to package your application as a JAR file.

See the tutorial Working with JAR files @se-edu/guides to learn how to create and use JAR files.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As you know, one of the objectives of the iP is to raise the quality of your code. We'll be learning about various ways to improve the code quality in the next few weeks, starting with coding standards.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

In-video quizzes

The Q+ icon indicates that the video has an in-video quiz. Submitting the in-video quiz can earn you bonus participation marks.

In-video quizzes are in only a small number of lecture videos that are more important than the rest. They are a very light way to engage you with the video a bit more than just passively watching.

Please watch the lecture video given below as it has some extra points not given in the text version.

Can explain the importance of code quality

Always code as if the person who ends up maintaining your code will be a violent psychopath who knows where you live. -- Martin Golding

Production code needs to be of high quality. Given how the world is becoming increasingly dependent on software, poor quality code is something no one can afford to tolerate.

Can explain the need for following a standard

One essential way to improve code quality is to follow a consistent style. That is why software engineers usually follow a strict coding standard (aka style guide).

The aim of a coding standard is to make the entire code base look like it was written by one person. A coding standard is usually specific to a programming language and specifies guidelines such as the locations of opening and closing braces, indentation styles and naming styles (e.g. whether to use Hungarian style, Pascal casing, Camel casing, etc.). It is important that the whole team/company uses the same coding standard and that the standard is generally not inconsistent with typical industry practices. If a company's coding standard is very different from what is typically used in the industry, new recruits will take longer to get used to the company's coding style.

IDEs can help to enforce some parts of a coding standard e.g. indentation rules.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

As promised last week, let's learn some more sophisticated ways of testing.

Can explain the need for early developer testing

Delaying testing until the full product is complete has a number of disadvantages:

- Locating the cause of a test case failure is difficult due to the larger search space; in a large system, the search space could be millions of lines of code, written by hundreds of developers! The failure may also be due to multiple inter-related bugs.

- Fixing a bug found during such testing could result in major rework, especially if the bug originated from the design or during requirements specification i.e. a faulty design or faulty requirements.

- One bug might 'hide' other bugs, which could emerge only after the first bug is fixed.

- The delivery may have to be delayed if too many bugs are found during testing.

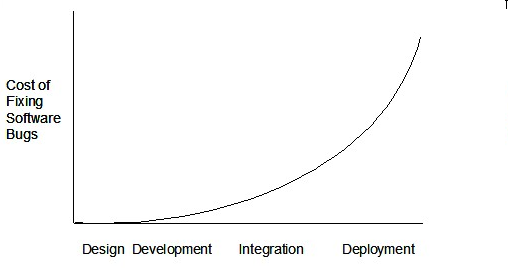

Therefore, it is better to do early testing, as hinted by the popular rule of thumb given below, also illustrated by the graph below it.

The earlier a bug is found, the easier and cheaper to have it fixed.

Such early testing software is usually, and often by necessity, done by the developers themselves i.e., developer testing.

Can explain test drivers

A test driver is the code that ‘drives’ the for the purpose of testing i.e. invoking the SUT with test inputs and verifying if the behavior is as expected.

PayrollTest ‘drives’ the Payroll class by sending it test inputs and verifies if the output is as expected.

public class PayrollTest {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

// test setup

Payroll p = new Payroll();

// test case 1

p.setEmployees(new String[]{"E001", "E002"});

// automatically verify the response

if (p.totalSalary() != 6400) {

throw new Error("case 1 failed ");

}

// test case 2

p.setEmployees(new String[]{"E001"});

if (p.totalSalary() != 2300) {

throw new Error("case 2 failed ");

}

// more tests...

System.out.println("All tests passed");

}

}

Can explain test automation tools

JUnit is a tool for automated testing of Java programs. Similar tools are available for other languages and for automating different types of testing.

This is an automated test for a Payroll class, written using JUnit libraries.

// other test methods

@Test

public void testTotalSalary() {

Payroll p = new Payroll();

// test case 1

p.setEmployees(new String[]{"E001", "E002"});

assertEquals(6400, p.totalSalary());

// test case 2

p.setEmployees(new String[]{"E001"});

assertEquals(2300, p.totalSalary());

// more tests...

}

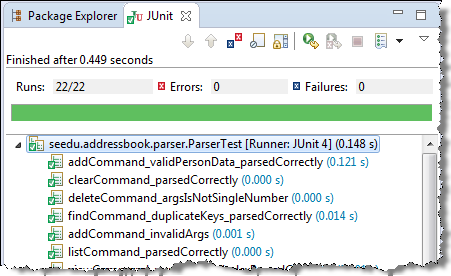

Most modern IDEs have integrated support for testing tools. The figure below shows the JUnit output when running some JUnit tests using the Eclipse IDE.

Can explain unit testing

Unit testing: testing individual units (methods, classes, subsystems, ...) to ensure each piece works correctly.

In OOP code, it is common to write one or more unit tests for each public method of a class.

Here are the code skeletons for a Foo class containing two methods and a FooTest class that contains unit tests for those two methods.

class Foo {

String read() {

// ...

}

void write(String input) {

// ...

}

}

class FooTest {

@Test

void read() {

// a unit test for Foo#read() method

}

@Test

void write_emptyInput_exceptionThrown() {

// a unit tests for Foo#write(String) method

}

@Test

void write_normalInput_writtenCorrectly() {

// another unit tests for Foo#write(String) method

}

}

import unittest

class Foo:

def read(self):

# ...

def write(self, input):

# ...

class FooTest(unittest.TestCase):

def test_read(self):

# a unit test for read() method

def test_write_emptyIntput_ignored(self):

# a unit test for write(string) method

def test_write_normalInput_writtenCorrectly(self):

# another unit test for write(string) method

Resources:

- Learning from Apple’s #gotofail Security Bug - How unit testing (and other good coding practices) could have prevented a major security bug.

Can use simple JUnit tests

When writing JUnit tests for a class Foo, the common practice is to create a FooTest class, which will contain various test methods for testing methods of the Foo class.

Suppose we want to write tests for the IntPair class below.

public class IntPair {

int first;

int second;

public IntPair(int first, int second) {

this.first = first;

this.second = second;

}

/**

* Returns the result of applying integer division first/second.

* @throws Exception if second is 0

*/

public int intDivision() throws Exception {

if (second == 0){

throw new Exception("Divisor is zero");

}

return first/second;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return first + "," + second;

}

}

Here's a IntPairTest class to match (using JUnit 5).

import org.junit.jupiter.api.Test;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.assertEquals;

import static org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.fail;

public class IntPairTest {

@Test

public void intDivision_nonZeroDivisor_success() throws Exception {

// normal division results in an integer answer 2

assertEquals(2, new IntPair(4, 2).intDivision());

// normal division results in a decimal answer 1.9

assertEquals(1, new IntPair(19, 10).intDivision());

// dividend is zero but devisor is not

assertEquals(0, new IntPair(0, 5).intDivision());

}

@Test

public void intDivision_zeroDivisor_exceptionThrown() {

try {

assertEquals(0, new IntPair(1, 0).intDivision());

fail(); // the test should not reach this line

} catch (Exception e) {

assertEquals("Divisor is zero", e.getMessage());

}

}

@Test

public void testStringConversion() {

assertEquals("4,7", new IntPair(4, 7).toString());

}

}

- Note how each test method is marked with a

@Testannotation. - Tests use

assertEquals(expected, actual)methods (provided by JUnit) to compare the expected output with the actual output. If they do not match, the test will fail.

JUnit comes with other similar methods such asassertNull,assertNotNull,assertTrue,assertFalseetc. [more ...] - Java code normally use camelCase for method names e.g.,

testStringConversionbut when writing test methods, sometimes another convention is used:

unitBeingTested_descriptionOfTestInputs_expectedOutcome

e.g.,intDivision_zeroDivisor_exceptionThrown - There are several ways to verify the code throws the correct exception. The second test method in the example above shows one of the simpler methods. If the exception is thrown, it will be caught and further verified inside the

catchblock. But if it is not thrown as expected, the test will reachfail()line and will fail as a result.

What to test for when writing tests? While test case design techniques is a separate topic altogether, it should be noted that the goal of these tests is to catch bugs in the code. Therefore, test using inputs that can trigger a potentially buggy path in the code. Another way to approach this is, to write tests such that if a future developer modified the method to unintentionally introduce a bug into it, at least one of the test should fail (thus alerting that developer to the mistake immediately).

In the example above, the IntPairTest class tests the IntPair#intDivision(int, int) method using several inputs, some even seemingly attempting to 'trick' the method into producing a wrong result. If the method still produces the correct output for such 'tricky' inputs (as well as 'normal' outputs), we can have a higher confidence on the method being correctly implemented.

However, also note that the current test cases do not (but probably should) test for the inputs (0, 0), to confirm that it throws the expected exception.

Resources:

- Recommended: JUnit tutorial @se-edu/guides explains how to use JUnit in your Java project.

- JUnit Official User Guide

- JUnit 5 Tutorial – Common Annotations With Examples - a short tutorial

- How to test private methods in Java? [ short answer ] [ long answer ]

Can use stubs to isolate an SUT from its dependencies

A proper unit test requires the unit to be tested in isolation so that bugs in the cannot influence the test i.e. bugs outside of the unit should not affect the unit tests.

If a Logic class depends on a Storage class, unit testing the Logic class requires isolating the Logic class from the Storage class.

Stubs can isolate the from its dependencies.

Stub: A stub has the same interface as the component it replaces, but its implementation is so simple that it is unlikely to have any bugs. It mimics the responses of the component, but only for a limited set of predetermined inputs. That is, it does not know how to respond to any other inputs. Typically, these mimicked responses are hard-coded in the stub rather than computed or retrieved from elsewhere, e.g. from a database.

Consider the code below:

class Logic {

Storage s;

Logic(Storage s) {

this.s = s;

}

String getName(int index) {

return "Name: " + s.getName(index);

}

}

interface Storage {

String getName(int index);

}

class DatabaseStorage implements Storage {

@Override

public String getName(int index) {

return readValueFromDatabase(index);

}

private String readValueFromDatabase(int index) {

// retrieve name from the database

}

}

Normally, you would use the Logic class as follows (note how the Logic object depends on a DatabaseStorage object to perform the getName() operation):

Logic logic = new Logic(new DatabaseStorage());

String name = logic.getName(23);

You can test it like this:

@Test

void getName() {

Logic logic = new Logic(new DatabaseStorage());

assertEquals("Name: John", logic.getName(5));

}

However, this logic object being tested is making use of a DataBaseStorage object which means a bug in the DatabaseStorage class can affect the test. Therefore, this test is not testing Logic in isolation from its dependencies and hence it is not a pure unit test.

Here is a stub class you can use in place of DatabaseStorage:

class StorageStub implements Storage {

@Override

public String getName(int index) {

if (index == 5) {

return "Adam";

} else {

throw new UnsupportedOperationException();

}

}

}

Note how the StorageStub has the same interface as DatabaseStorage, but is so simple that it is unlikely to contain bugs, and is pre-configured to respond with a hard-coded response, presumably, the correct response DatabaseStorage is expected to return for the given test input.

Here is how you can use the stub to write a unit test. This test is not affected by any bugs in the DatabaseStorage class and hence is a pure unit test.

@Test

void getName() {

Logic logic = new Logic(new StorageStub());

assertEquals("Name: Adam", logic.getName(5));

}

In addition to Stubs, there are other type of replacements you can use during testing, e.g. Mocks, Fakes, Dummies, Spies.

Resources:

- Mocks Aren't Stubs by Martin Fowler -- An in-depth article about how Stubs differ from other types of test helpers.

Guidance for the item(s) below:

While the JUnit concepts mentioned in the topic below are not strictly needed for the course projects, it is good to be aware of them so that you try some of them when applicable.